Back مغالطة معدل الأساس Arabic Prävalenzfehler German Falacia de la frecuencia base Spanish غفلت از نرخ پایه Persian Oubli de la fréquence de base French כשל הסתברות קודמת HE Fallacia del tasso di base Italian 기저율 오류 Korean Zaniedbywanie miarodajności Polish Falácia da taxa-base Portuguese

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (July 2023) |

The base rate fallacy, also called base rate neglect[2] or base rate bias, is a type of fallacy in which people tend to ignore the base rate (e.g., general prevalence) in favor of the individuating information (i.e., information pertaining only to a specific case).[3] For example, if someone hears that a friend is very shy and quiet, they might think the friend is more likely to be a librarian than a salesperson, even though there are far more salespeople than librarians overall - hence making it more likely that their friend is actually a salesperson. Base rate neglect is a specific form of the more general extension neglect.

It is also called the prosecutor's fallacy or defense attorney's fallacy when applied to the results of statistical tests (such as DNA tests) in the context of law proceedings. These terms were introduced by William C. Thompson and Edward Schumann in 1987,[4][5] although it has been argued that their definition of the prosecutor's fallacy extends to many additional invalid imputations of guilt or liability that are not analyzable as errors in base rates or Bayes's theorem.[6]

- ^ "COVID-19 Cases, Hospitalizations, and Deaths by Vaccination Status" (PDF). Washington State Department of Health. 2023-01-18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-01-26. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

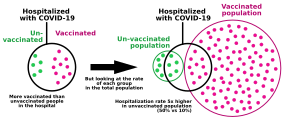

If the exposure to COVID-19 stays the same, as more individuals are vaccinated, more cases, hospitalizations, and deaths will be in vaccinated individuals, as they will continue to make up more and more of the population. For example, if 100% of the population was vaccinated, 100% of cases would be among vaccinated people.

- ^ Welsh, Matthew B.; Navarro, Daniel J. (2012). "Seeing is believing: Priors, trust, and base rate neglect". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 119 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.04.001. hdl:2440/41190. ISSN 0749-5978.

- ^ "Logical Fallacy: The Base Rate Fallacy". Fallacyfiles.org. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ^ Thompson, W.C.; Schumann, E.L. (1987). "Interpretation of Statistical Evidence in Criminal Trials: The Prosecutor's Fallacy and the Defense Attorney's Fallacy". Law and Human Behavior. 2 (3): 167. doi:10.1007/BF01044641. JSTOR 1393631. S2CID 147472915.

- ^ Fountain, John; Gunby, Philip (February 2010). "Ambiguity, the Certainty Illusion, and Gigerenzer's Natural Frequency Approach to Reasoning with Inverse Probabilities" (PDF). University of Canterbury. p. 6.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Suss, Richard A. (October 4, 2023). "The Prosecutor's Fallacy Framed as a Sample Space Substitution". OSF Preprints. doi:10.31219/osf.io/cs248.