Back Sentour (kleinplaneet) Afrikaans قنطور (كوكب صغير) Arabic Centauru (astronomía) AST Zentauren (Astronomie) BAR Кентаўры (астэроіды) Byelorussian Кентаўры (плянэтоіды) BE-X-OLD Кентавър (планетоид) Bulgarian Kentauri BS Centaure (astronomia) Catalan Skupina kentaurů Czech

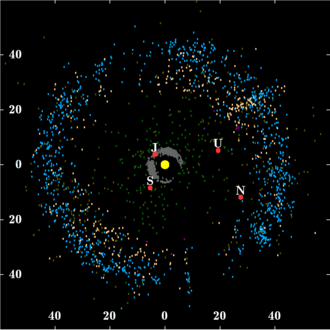

The centaurs orbit generally inwards of the Kuiper belt and outside the Jupiter trojans.

| Sun Jupiter trojans (6,178) Scattered disc (>300) Neptune trojans (9) | Giant planets: · Jupiter (J) · Saturn (S) · Uranus (U) · Neptune (N) Centaurs (44,000) Kuiper belt (>100,000) |

|

In planetary astronomy, a centaur is a small Solar System body that orbits the Sun between Jupiter and Neptune and crosses the orbits of one or more of the giant planets. Centaurs generally have unstable orbits because they cross or have crossed the orbits of the giant planets; almost all their orbits have dynamic lifetimes of only a few million years,[1] but there is one known centaur, 514107 Kaʻepaokaʻawela, which may be in a stable (though retrograde) orbit.[2][note 1] Centaurs typically exhibit the characteristics of both asteroids and comets. They are named after the mythological centaurs that were a mixture of horse and human. Observational bias toward large objects makes determination of the total centaur population difficult. Estimates for the number of centaurs in the Solar System more than 1 km in diameter range from as low as 44,000[1] to more than 10,000,000.[4][5]

The first centaur to be discovered, under the definition of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the one used here, was 944 Hidalgo in 1920. However, they were not recognized as a distinct population until the discovery of 2060 Chiron in 1977. The largest confirmed centaur is 10199 Chariklo, which at 260 kilometers in diameter is as big as a mid-sized main-belt asteroid, and is known to have a system of rings. It was discovered in 1997.

No centaur has been photographed up close, although there is evidence that Saturn's moon Phoebe, imaged by the Cassini probe in 2004, may be a captured centaur that originated in the Kuiper belt.[6] In addition, the Hubble Space Telescope has gleaned some information about the surface features of 8405 Asbolus.

Ceres may have originated in the region of the outer planets,[7] and if so might be considered an ex-centaur, but the centaurs seen today all originated elsewhere.

Of the objects known to occupy centaur-like orbits, approximately 30 have been found to display comet-like dust comas, with three, 2060 Chiron, 60558 Echeclus, and 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1, having detectable levels of volatile production in orbits entirely beyond Jupiter.[8] Chiron and Echeclus are therefore classified as both centaurs and comets, while Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 has always held a comet designation. Other centaurs, such as 52872 Okyrhoe, are suspected of having shown comas. Any centaur that is perturbed close enough to the Sun is expected to become a comet.

- ^ a b Horner, J.; Evans, N.W.; Bailey, M. E. (2004). "Simulations of the Population of Centaurs I: The Bulk Statistics". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 354 (3): 798–810. arXiv:astro-ph/0407400. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.354..798H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08240.x. S2CID 16002759.

- ^ Fathi Namouni and Maria Helena Moreira Morais (May 2, 2018). "An interstellar origin for Jupiter's retrograde co-orbital asteroid". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 477 (1): L117–L121. arXiv:1805.09013. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.477L.117N. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/sly057. S2CID 54224209.

- ^ Billings, Lee (21 May 2018). "Astronomers Spot Potential 'Interstellar' Asteroid Orbiting Backward Around the Sun". Scientific American. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Sarid2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Sheppard, S.; Jewitt, D.; Trujillo, C.; Brown, M.; Ashley, M. (2000). "A Wide-Field CCD Survey for Centaurs and Kuiper Belt Objects". The Astronomical Journal. 120 (5): 2687–2694. arXiv:astro-ph/0008445. Bibcode:2000AJ....120.2687S. doi:10.1086/316805. S2CID 119337442.

- ^ Jewitt, David; Haghighipour, Nader (2007). "Irregular Satellites of the Planets: Products of Capture in the Early Solar System" (PDF). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 45 (1): 261–95. arXiv:astro-ph/0703059. Bibcode:2007ARA&A..45..261J. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.44.051905.092459. S2CID 13282788. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-19.

- ^ "Dawn at Ceres:What Have we Learned?" (PDF). Space Studies Board. National Academies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-13. Retrieved 2023-10-11.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Wierzchos2017was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).