Back Kirkwoodgaping Afrikaans فجوة كيركوود Arabic Шчыліны Кірквуда Byelorussian Llacuna de Kirkwood Catalan Kirkwoodova mezera Czech Kirkwoodlücke German Malpleno de Kirkwood Esperanto Huecos de Kirkwood Spanish Kirkwooden hutsuneak Basque شکاف کرکوود Persian

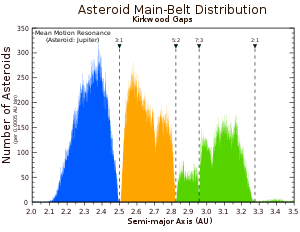

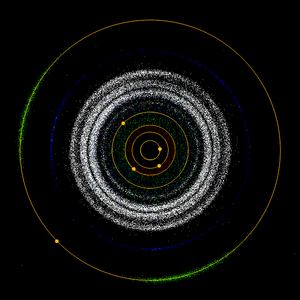

inner main-belt (a < 2.5 AU)

intermediate main-belt (2.5 AU < a < 2.82 AU)

outer main-belt (a > 2.82 AU)

A Kirkwood gap is a gap or dip in the distribution of the semi-major axes (or equivalently of the orbital periods) of the orbits of main-belt asteroids. They correspond to the locations of orbital resonances with Jupiter.

For example, there are very few asteroids with semimajor axis near 2.50 AU, period 3.95 years, which would make three orbits for each orbit of Jupiter (hence, called the 3:1 orbital resonance). Other orbital resonances correspond to orbital periods whose lengths are simple fractions of Jupiter's. The weaker resonances lead only to a depletion of asteroids, while spikes in the histogram are often due to the presence of a prominent asteroid family (see List of asteroid families).

The gaps were first noticed in 1866 by Daniel Kirkwood, who also correctly explained their origin in the orbital resonances with Jupiter while a professor at Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania.[1]

Most of the Kirkwood gaps are depleted, unlike the mean-motion resonances (MMR) of Neptune or Jupiter's 3:2 resonance, that retain objects captured during the giant planet migration of the Nice model. The loss of objects from the Kirkwood gaps is due to the overlapping of the ν5 and ν6 secular resonances within the mean-motion resonances. The orbital elements of the asteroids vary chaotically as a result and evolve onto planet-crossing orbits within a few million years.[2] The 2:1 MMR has a few relatively stable islands within the resonance, however. These islands are depleted due to slow diffusion onto less stable orbits. This process, which has been linked to Jupiter and Saturn being near a 5:2 resonance, may have been more rapid when Jupiter's and Saturn's orbits were closer together.[3]

More recently, a relatively small number of asteroids have been found to possess high eccentricity orbits which do lie within the Kirkwood gaps. Examples include the Alinda and Griqua groups. These orbits slowly increase their eccentricity on a timescale of tens of millions of years, and will eventually break out of the resonance due to close encounters with a major planet. This is why asteroids are rarely found in the Kirkwood gaps.