Back قائمة مواقع التراث العالمي المعرضة للخطر Arabic Təhlükədə olan ümumdünya irsi obyektlərinin siyahısı Azerbaijani বিপর্যয়ের সম্মুখীন বিশ্ব ঐতিহ্যের তালিকা Bengali/Bangla Llista del Patrimoni de la Humanitat en perill Catalan Seznam světového dědictví v ohrožení Czech UNESCOs Verdensarvsliste (I fare) Danish Liste des gefährdeten Welterbes German Ruĝa Listo de la Monda Heredaĵo Esperanto Anexo:Patrimonio de la Humanidad en peligro Spanish Ohustatud maailmapärandiobjektide nimistu Estonian

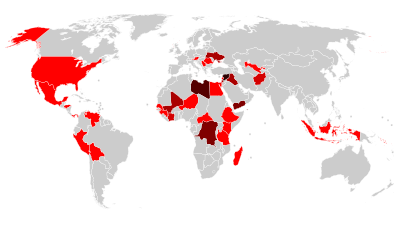

- Six or more sites

- Five sites

- Four sites

- Three sites

- Two sites

- One site

The List of World Heritage in Danger is compiled by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) through the World Heritage Committee according to Article 11.4 of the World Heritage Convention,[nb 1] which was established in 1972 to designate and manage World Heritage Sites. Entries in the list are threatened World Heritage Sites for the conservation of which major operations are required and for which "assistance has been requested".[1] The list is intended to increase international awareness of the threats and to encourage counteractive measures.[2] Threats to a site can be either proven imminent threats or potential dangers that could have adverse effects on a site.

In the case of natural sites, ascertained dangers include the serious decline in the population of an endangered or other valuable species or the deterioration of natural beauty or scientific value of a property caused by human activities such as logging, pollution, settlement, mining, agriculture and major public works. Ascertained dangers for cultural properties include serious deterioration of materials, structure, ornaments or architectural coherence and the loss of historical authenticity or cultural significance. Potential dangers for both cultural and natural sites include development projects, armed conflicts, insufficient management systems or changes in the legal protective status of the properties. In the case of cultural sites, gradual changes due to geology, climate or environment can also be potential dangers.[3]

Before a property is inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger, its condition is assessed and a potential programme for corrective measures is developed in cooperation with the State Party involved. The final decision about inscription is made by the committee. Financial support from the World Heritage Fund may be allocated by the committee for listed properties. The state of conservation is reviewed on a yearly basis, after which the committee may request additional measures, delete the property from the list if the threats have ceased or consider deletion from both the List of World Heritage in Danger and the World Heritage List.[3] Of the three former UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the Dresden Elbe Valley and the Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City were delisted after placement on the List of World Heritage in Danger while the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary was directly delisted.[4][5] Some sites have been designated as World Heritage Sites and World Heritage in Danger in the same year, such as the Church of the Nativity, traditionally considered to be the birthplace of Jesus.

In some cases, danger listing has sparked conservation efforts and prompted the release of funds, resulting in a positive development for sites such as the Galápagos Islands and Yellowstone National Park, both of which have subsequently been removed from the List of World Heritage in Danger. Despite this, the list itself and UNESCO's implementation of it have been the focus of criticism.[6][7] In particular, States Parties and other stakeholders of World Heritage Sites have questioned the authority of the Committee to declare a site in danger without their consent.[8] Until 1992, when UNESCO set a precedent by placing several sites on the danger list against their wishes, States Parties would have submitted a programme of corrective measures before a site could be listed.[9] Instead of being used as intended, the List of World Heritage in Danger is perceived by some states as a black list and according to Christina Cameron, Professor at the School of Architecture, Canada Research Chair on Built Heritage, University of Montreal, has been used as political tool to get the attention of States Parties.[10][11] The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) notes that UNESCO has referenced the List of World Heritage in Danger (without actually listing the site) in a number of cases where the threat could be easily addressed by the State Party.[12] The Union also argues that keeping a site listed as endangered over a long period is questionable and that other mechanisms for conservation should be sought in these cases.[13]

As of April 2024[update], there are 56 entries (16 natural, 40 cultural) on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Arranged by the UNESCO regions, 23 of the listed sites are located in the Arab States, 14 in Africa, 6 in Latin America and the Caribbean, 6 in Asia and the Pacific, and 7 in Europe and North America. The majority of the endangered natural sites (11) are located in Africa.[14][15] The list encompasses sites that have been identified as facing threats to their integrity, which could stem from natural disasters, armed conflict, neglect, pollution, unsustainable tourism, or other dangers. Among the sites, the impacts of armed conflict are evident in countries like Syria, with several sites including the Ancient City of Aleppo and the Ancient Villages of Northern Syria marked as endangered due to the Syrian Civil War. In Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo sees multiple listings due to threats like military conflict and environmental degradation affecting its national parks.[16]

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).

- ^ "Convention concerning the protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ "List of World Heritage in Danger". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention" (PDF). UNESCO. January 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ "Oman's Arabian Oryx Sanctuary: first site ever to be deleted from UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ "Dresden is deleted from UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ Chape, Spalding & Jenkins 2008, p. 87

- ^ Timothy & Nyaupane 2009, p. 83

- ^ IUCN 2009, pp. 2–3

- ^ Chape, Spalding & Jenkins 2008, p. 86

- ^ Thorsell, J. W.; Sawyer, Jacqueline (1992). World heritage 20 years later (illustrated ed.). IUCN. p. 23. ISBN 978-2-8317-0109-7. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ IUCN 2009, p. 0

- ^ IUCN 2009, pp. 18–19

- ^ IUCN 2009, pp. 19–20

- ^ "List of World Heritage in Danger". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "World Heritage List Statistics". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "UNESCO World Heritage Centre - List of World Heritage in Danger". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2 April 2024.