Back Махатма Ганди ADY Mahatma Gandhi Afrikaans Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi ALS ማህተማ ጋንዲ Amharic Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi AN Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi ANG महात्मा गांधी ANP مهاتما غاندي Arabic لماهاطما ݣاندي ARY مهاتما جاندى ARZ

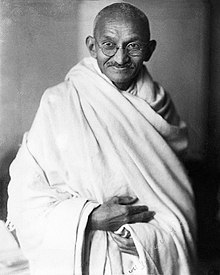

| Mahatma Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi મોહનદાસ કરમચંદ ગાંધી | |

|---|---|

| Nome completo | Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi |

| Pseudônimo(s) | Mahatma Gandhi, Bapu ji, Gandhi ji |

| Conhecido(a) por | Movimento de independência da Índia, resistência não violenta |

| Nascimento | 2 de outubro de 1869 Porbandar, Distrito de Kathiawar, Índia Britânica |

| Morte | 30 de janeiro de 1948 (78 anos) Nova Deli, Deli, Domínio da Índia |

| Causa da morte | Assassinato |

| Nacionalidade | Indiano |

| Progenitores | Mãe: Putlibai Gandhi Pai: Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi |

| Cônjuge | Kasturba Gandhi (1883–1944) |

| Filho(a)(s) | 4 |

| Alma mater | University College London[1] Inner Temple |

| Ocupação | |

| Outras ocupações | Presidente do Congresso Nacional Indiano |

| Período de atividade | 1919–1948 |

| Principais trabalhos | The Story of My Experiments with Truth |

| Prêmios | Pessoa do Ano (1930) |

| Assinatura | |

| |

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Porbandar, 2 de outubro de 1869 – Nova Déli, 30 de janeiro de 1948) foi um advogado,[2] estadista,[3][4] e líder espiritual[5] indiano. Considerado também um líder religioso,[6] além de nacionalista, anticolonialista[7] e especialista em ética política indiana.[8] Ficou conhecido por ter empregado a resistência não violenta para liderar a campanha bem-sucedida pela independência da Índia do Reino Unido[9] e, por sua vez, por inspirar movimentos pelos direitos civis e pela liberdade em todo o mundo. O honorífico Mahātmā (sânscrito: "de grande alma", "venerável"),[10] aplicado a ele pela primeira vez em 1914 na África do Sul,[11] é agora usado em todo o mundo. O aniversário de Gandhi, 2 de outubro, é comemorado na Índia como Gandhi Jayanti, um feriado nacional e em todo o mundo como o Dia Internacional da Não Violência. Gandhi nasceu e foi criado em uma família hindu no litoral de Guzerate, oeste da Índia, e se formou em direito no Inner Temple, Londres. É comumente, embora não formalmente considerado o Pai da Pátria indiana[12][13] e também é chamado de Bapu[14] (Guzerate: carinho por pai,[15] papa[15][16]).

Seguia o princípio da não violência[17] incorporado à desobediência civil,[18] e empregou pela primeira vez a desobediência civil não violenta como advogado expatriado na África do Sul, na luta da comunidade indiana pelos direitos civis. Após seu retorno à Índia em 1915, começou a organizar camponeses, agricultores e trabalhadores urbanos para protestar contra o imposto sobre a terra e a discriminação excessiva. Assumindo a liderança do Congresso Nacional Indiano em 1921, Gandhi liderou campanhas nacionais para várias causas sociais e para alcançar o Swaraj ou o autogoverno.[19]

Gandhi levou os indianos a desafiar o imposto salino cobrado pelos ingleses com a Marcha do Sal, de 400 km, em 1930, e mais tarde pedindo aos britânicos que abandonassem a Índia em 1942. Foi preso por muitos anos, em várias ocasiões, na África do Sul e na Índia. Vivia modestamente em uma comunidade residencial autossuficiente e usava o dhoti e o xale indiano tradicional, entrelaçados com fios feitos à mão em um charkha. Comia comida vegetariana simples e também realizou longos jejuns como um meio de autopurificação e protesto político.

A visão de Gandhi de uma Índia independente baseada no pluralismo religioso foi desafiada no início da década de 1940 por um novo nacionalismo muçulmano que exigia uma pátria muçulmana separada da Índia.[20] Em agosto de 1947, o Reino Unido concedeu a independência, mas o Império Britânico da Índia[20] foi dividido em dois domínios, a Índia de maioria hindu e o Paquistão de maioria muçulmana.[21] Como muitos indianos, muçulmanos e sikhs deslocados chegaram às suas novas terras, a violência religiosa irrompeu, especialmente em Panjabe e em Bengala. Evitando a celebração oficial da independência em Delhi, Gandhi visitou as áreas afetadas, tentando proporcionar consolo. Nos meses seguintes, ele realizou várias greves de fome para deter a violência religiosa. O último deles, realizado em 12 de janeiro de 1948, quando tinha 78 anos, também teve o objetivo indireto de pressionar a Índia a pagar alguns ativos em dinheiro devidos ao Paquistão.[22] Alguns indianos pensavam que Gandhi era muito complacente com os muçulmanos.[22][23] Entre eles estava Nathuram Godse, um nacionalista hindu, que assassinou Gandhi em 30 de janeiro de 1948, disparando três vezes contra seu peito.[23]

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Shaw; Timothy J. Demy (2017). War and Religion: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict. [S.l.]: ABC-CLIO. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-61069-517-6

- ↑ B. R. Nanda (2019). «Mahatma Gandhi». Encyclopædia Britannica.

Mahatma Gandhi, byname of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, (born October 2, 1869, Porbandar, India—died January 30, 1948, Delhi), Indian lawyer, politician, ...

- ↑ Susan Ratcliffe (2018). «Mahatma Gandhi 1869–1948». Oxford Essential Quotations

- ↑ Jiwatram Bhagwandas Kripalani (1951). «Gandhi the Statesman»

- ↑ «Mahatma Gandhi». Oxford Essential Reference

- ↑ Agência Folha (1999). «Filhos de Gandhy promete inovações». Folha de S.Paulo

- ↑ Ganguly, Debjani; Docker, John (25 de março de 2008). Rethinking Gandhi and Nonviolent Relationality: Global Perspectives. [S.l.]: Routledge. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-134-07431-0.

... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti-colonial nationalist politics in the twentieth-century in ways that neither indigenous nor westernized Indian nationalists could.

- ↑ Parel, Anthony J (2016). Pax Gandhiana: The Political Philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi. [S.l.]: Oxford University Press. pp. 202–. ISBN 978-0-19-049146-8.

Gandhi staked his reputation as an original political thinker on this specific issue. Hitherto, violence had been used in the name of political rights, such as in street riots, regicide, or armed revolutions. Gandhi believes there is a better way of securing political rights, that of nonviolence, and that this new way marks an advance in political ethics.

- ↑ Stein, Burton (2010). A History of India. [S.l.]: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 289–. ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1.

Gandhi was the leading genius of the later, and ultimately successful, campaign for India’s independence.

- ↑ McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993). The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary. [S.l.]: Oxford University Press. p. 799. ISBN 978-0-19-864339-5. Consultado em 18 de agosto de 2019. Cópia arquivada em 12 de outubro de 2013.

(mahā- (S. "great, mighty, large, ..., eminent") + ātmā (S. "1.soul, spirit; the self, the individual; the mind, the heart; 2. the ultimate being."): "high-souled, of noble nature; a noble or venerable man."

- ↑ Gandhi 2006, p. 172: "... Kasturba would accompany Gandhi on his departure from Cape Town for England in July 1914 en route to India. ... In different South African towns (Pretoria, Cape Town, Bloemfontein, Johannesburg, and the Natal cities of Durban and Verulam), the struggle's martyrs were honoured and the Gandhi's bade farewell. Addresses in Durban and Verulam referred to Gandhi as a 'Mahatma', 'great soul'. He was seen as a great soul because he had taken up the poor's cause. The whites too said good things about Gandhi, who predicted a future for the Empire if it respected justice." (p. 172).

- ↑ «Gandhi not formally conferred 'Father of the Nation' title: Govt». The Indian Express. 11 de julho de 2012. Cópia arquivada em 6 de setembro de 2014

- ↑ «Constitution doesn't permit 'Father of the Nation' title: Government». The Times of India. 26 de outubro de 2012. Cópia arquivada em 7 de janeiro de 2017

- ↑ Nehru, Jawaharlal. An Autobiography. [S.l.]: Bodley Head

- ↑ a b McAllister, Pam (1982). Reweaving the Web of Life: Feminism and Nonviolence. [S.l.]: New Society Publishers. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-86571-017-7. Consultado em 18 de agosto de 2019. Cópia arquivada em 12 de outubro de 2013.

"With love, Yours, Bapu (You closed with the term of endearment used by your close friends, the term you used with all the movement leaders, roughly meaning 'Papa'." Another letter written in 1940 shows similar tenderness and caring.

- ↑ Eck, Diana L. (2003). Encountering God: A Spiritual Journey from Bozeman to Banaras. [S.l.]: Beacon Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8070-7301-8. Consultado em 18 de agosto de 2019. Cópia arquivada em 12 de outubro de 2013.

"... his niece Manu, who, like others called this immortal Gandhi 'Bapu,' meaning not 'father,' but the familiar, 'daddy'." (p. 210)

- ↑ «Dia Internacional da Não-Violência destaca legado pacífico de Gandhi». Nações Unidas Brasil. 3 de outubro de 2022

- ↑ «Desobediência civil: Ghandi, Luther King e luta pacífica». educacao.uol.com.br. Consultado em 10 de abril de 2024

- ↑ Maeleine Slade, Mirabehn. Gleanings Gathered at Bapu's Feet. Ahmedabad: Navjivan publications. Consultado em 18 de agosto de 2019

- ↑ a b Khan, Yasmin (2007). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. [S.l.]: Yale University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-300-12078-3. Consultado em 18 de agosto de 2019.

"the Muslim League had only caught on among South Asian Muslims during the Second World War. ... By the late 1940s, the League and the Congress had impressed in the British their own visions of a free future for Indian people. ... one, articulated by the Congress, rested on the idea of a united, plural India as a home for all Indians and the other, spelt out by the League, rested on the foundation of Muslim nationalism and the carving out of a separate Muslim homeland." (p. 18)

- ↑ Khan, Yasmin (2007). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. [S.l.]: Yale University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-300-12078-3. Consultado em 18 de agosto de 2019.

"South Asians learned that the British Indian empire would be partitioned on 3 June 1947. They heard about it on the radio, from relations and friends, by reading newspapers and, later, through government pamphlets. Among a population of almost four hundred million, where the vast majority lived in the countryside, ..., it is hardly surprising that many ... did not hear the news for many weeks afterwards. For some, the butchery and forced relocation of the summer months of 1947 may have been the first they know about the creation of the two new states rising from the fragmentary and terminally weakened British empire in India." (p. 1)

- ↑ a b Brown 1991, p. 380: "Despite and indeed because of his sense of helplessness Delhi was to be the scene of what he called his greatest fast. ... His decision was made suddenly, though after considerable thought – he gave no hint of it even to Nehru and Patel who were with him shortly before he announced his intention at a prayer-meeting on 12 January 1948. He said he would fast until communal peace was restored, real peace rather than the calm of a dead city imposed by police and troops. Patel and the government took the fast partly as condemnation of their decision to withhold a considerable cash sum still outstanding to Pakistan as a result of the allocation of undivided India's assets, because the hostilities that had broken out in Kashmir; ... But even when the government agreed to pay out the cash, Gandhi would not break his fast: that he would only do after a large number of important politicians and leaders of communal bodies agreed to a joint plan for restoration of normal life in the city.".

- ↑ a b Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. [S.l.]: Taylor & Francis. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-7007-1267-0. Consultado em 18 de agosto de 2019. Cópia arquivada em 12 de outubro de 2013.

"The apotheosis of this contrast is the assassination of Gandhi in 1948 by a militant Nathuram Godse, on the basis of his 'weak' accommodationist approach towards the new state of Pakistan." (p. 544)