Back Go Afrikaans Go (Spiel) ALS ጎ Amharic Go AN غو Arabic Go AST बदूक AWA Qo Azerbaijani قو (اویون) AZB Го Bashkir

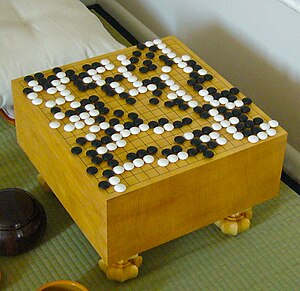

Go is played on a grid (usually 19×19). Game pieces (stones) are played on the grid line intersections. | |

| Years active | 548 BC (earliest record) to present |

|---|---|

| Genres | |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | Minimal |

| Playing time |

|

| Chance | None |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics, elementary arithmetic |

| Synonyms |

|

| a Some professional games exceed 16 hours and are played in sessions spread over two days. | |

| Go | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 圍棋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 围棋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | 'encirclement board game' | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | མིག་མངས | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | cờ vây | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 碁圍 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 바둑 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Katakana |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Go is an abstract strategy board game for two players in which the aim is to capture more territory than the opponent by fencing off empty space. The game was invented in China more than 2,500 years ago and is believed to be the oldest board game continuously played to the present day.[1][2][3][4][5] A 2016 survey by the International Go Federation's 75 member nations found that there are over 46 million people worldwide who know how to play Go, and over 20 million current players, the majority of whom live in East Asia.[6]

The playing pieces are called stones. One player uses the white stones and the other black. The players take turns placing their stones on the vacant intersections (points) on the board. Once placed, stones may not be moved, but captured stones are immediately removed from the board. A single stone (or connected group of stones) is captured when surrounded by the opponent's stones on all orthogonally adjacent points. [7] The game proceeds until neither player wishes to make another move.

When a game concludes, the winner is determined by counting each player's surrounded territory along with captured stones and komi (points added to the score of the player with the white stones as compensation for playing second).[8] Games may also end by resignation.[9]

The standard Go board has a 19×19 grid of lines, containing 361 points. Beginners often play on smaller 9×9 and 13×13 boards,[10] and archaeological evidence shows that the game was played in earlier centuries on a board with a 17×17 grid. Boards with a 19×19 grid had become standard, however, by the time the game reached Korea in the 5th century CE and Japan in the 7th century CE.[11]

Go was considered one of the four essential arts of the cultured aristocratic Chinese scholars in antiquity. The earliest written reference to the game is generally recognized as the historical annal Zuo Zhuan[12][13] (c. 4th century BCE).[14]

Despite its relatively simple rules, Go is extremely complex. Compared to chess, Go has both a larger board with more scope for play and longer games and, on average, many more alternatives to consider per move. The number of legal board positions in Go has been calculated to be approximately 2.1×10170,[15][a] which is far greater than the number of atoms in the observable universe, which is estimated to be on the order of 1080.[17]

| Part of a series on |

| Go |

|---|

|

| Game specifics |

|

| History and culture |

| Players and organizations |

| Computers and mathematics |

- ^ "A Brief History of Go". American Go Association. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Shotwell, Peter (2008), The Game of Go: Speculations on its Origins and Symbolism in Ancient China (PDF), American Go Association, archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2013

- ^ "The Legends of the Sage Kings and Divination". GoBase.org. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ "A Brief History of Go | British Go Association". www.britgo.org. Retrieved 2023-12-16.

- ^ "The Ancient Chinese Game of Go". www.china.org.cn. Retrieved 2023-12-16.

- ^ The International Go Federation (February 2016). "Go Population Survey" (PDF). intergofed.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Iwamoto 1977, p. 22.

- ^ Iwamoto 1977, p. 18.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Matthews 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Cho Chikun 1997, p. 18.

- ^ Burton, Watson (April 15, 1992). The Tso Chuan. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-06715-7.

- ^ Fairbairn 1995, p. [page needed].

- ^ "Warring States Project Chronology #2". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ^ Tromp, John; Farnebäck, Gunnar (January 31, 2016). "Combinatorics of Go" (PDF). tromp.github.io. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Allis 1994, pp. 158–161, 171, 174, §§6.2.4, 6.3.9, 6.3.12

- ^ Lee, Kai-Fu (September 25, 2018). AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9781328546395. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).