Back Swaartegolf Afrikaans موجة ثقالية Arabic মহাকৰ্ষণিক তৰংগ Assamese Гравітацыйная хваля Byelorussian Гравитационна вълна Bulgarian মহাকর্ষীয় তরঙ্গ Bengali/Bangla Gravitacijski talas BS Ona gravitacional Catalan Gravitační vlny Czech Ton ddisgyrchol Welsh

| General relativity |

|---|

|

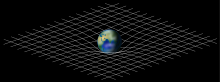

Gravitational waves are waves of the intensity of gravity that are generated by the accelerated masses of binary stars and other motions of gravitating masses, and propagate as waves outward from their source at the speed of light. They were first proposed by Oliver Heaviside in 1893 and then later by Henri Poincaré in 1905 as the gravitational equivalent of electromagnetic waves.[1] Gravitational waves are sometimes called gravity waves,[2] but gravity waves typically refer to displacement waves in fluids. In 1916[3][4] Albert Einstein demonstrated that gravitational waves result from his general theory of relativity as ripples in spacetime.[5][6]

Gravitational waves transport energy as gravitational radiation, a form of radiant energy similar to electromagnetic radiation.[7] Newton's law of universal gravitation, part of classical mechanics, does not provide for their existence, since that law is predicated on the assumption that physical interactions propagate instantaneously (at infinite speed) – showing one of the ways the methods of Newtonian physics are unable to explain phenomena associated with relativity.

The first indirect evidence for the existence of gravitational waves came in 1974 from the observed orbital decay of the Hulse–Taylor binary pulsar, which matched the decay predicted by general relativity as energy is lost to gravitational radiation. In 1993, Russell A. Hulse and Joseph Hooton Taylor Jr. received the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery.

The first direct observation of gravitational waves was made in 2015, when a signal generated by the merger of two black holes was received by the LIGO gravitational wave detectors in Livingston, Louisiana, and in Hanford, Washington. The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics was subsequently awarded to Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Barry Barish for their role in the direct detection of gravitational waves.

In gravitational-wave astronomy, observations of gravitational waves are used to infer data about the sources of gravitational waves. Sources that can be studied this way include binary star systems composed of white dwarfs, neutron stars,[8][9] and black holes; events such as supernovae; and the formation of the early universe shortly after the Big Bang.

- ^ "Sur la dynamique de l'électron - Note de Henri Poincaré publiée dans les Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences de la séance du 5 juin 1905 - Membres de l'Académie des sciences depuis sa création" [On the dynamics of the electron - Note by Henri Poincaré published in the Reports of the Academy of Sciences of the session of June 5, 1905 - Members of the Academy of Sciences since its creation] (PDF). www.academie-sciences.fr (in French). Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ Davies, Paul (1980). The search for gravity waves. Cambridge [Eng.]; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23197-8.

- ^ Einstein, A (June 1916). "Näherungsweise Integration der Feldgleichungen der Gravitation". Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Berlin. part 1: 688–696. Bibcode:1916SPAW.......688E. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2014-11-15.

- ^ Einstein, A (1918). "Über Gravitationswellen". Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Berlin. part 1: 154–167. Bibcode:1918SPAW.......154E. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2014-11-15.

- ^ Finley, Dave. "Einstein's gravity theory passes toughest test yet: Bizarre binary star system pushes study of relativity to new limits". Phys.Org.

- ^ The Detection of Gravitational Waves using LIGO, B. Barish Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Einstein, Albert; Rosen, Nathan (January 1937). "On gravitational waves". Journal of the Franklin Institute. 223 (1): 43–54. Bibcode:1937FrInJ.223...43E. doi:10.1016/S0016-0032(37)90583-0.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (29 June 2021). "A Black Hole Feasted on a Neutron Star. 10 Days Later, It Happened Again – Astronomers had long suspected that collisions between black holes and dead stars occurred, but they had no evidence until a pair of recent detections". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Abbott, R.; et al. (29 June 2021). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from Two Neutron Star–Black Hole Coalescences". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 915 (1): L5. arXiv:2106.15163. Bibcode:2021ApJ...915L...5A. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac082e. S2CID 235670241.