Back تاريخ الزراعة Arabic تاريخ الزراعه ARZ Historia de l'agricultura AST Kənd təsərrüfatı tarixi Azerbaijani اکینچیلیک تاریخی AZB কৃষিকাজের ইতিহাস Bengali/Bangla Història de l'agricultura Catalan Dějiny zemědělství Czech Landbrugshistorie Danish Geschichte der Landwirtschaft German

| Agriculture |

|---|

|

|

|

| Rural Society |

|---|

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of taxa. At least eleven separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin. The development of agriculture about 12,000 years ago changed the way humans lived. They switched from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to permanent settlements and farming.[1]

Wild grains were collected and eaten from at least 104,000 years ago.[2] However, domestication did not occur until much later. The earliest evidence of small-scale cultivation of edible grasses is from around 21,000 BC with the Ohalo II people on the shores of the Sea of Galilee.[3] By around 9500 BC, the eight Neolithic founder crops – emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chickpeas, and flax – were cultivated in the Levant.[4] Rye may have been cultivated earlier, but this claim remains controversial.[5] Regardless, rye's spread from Southwest Asia to the Atlantic was independent of the Neolithic founder crop package.[6] Rice was domesticated in China by 6200 BC[7] with earliest known cultivation from 5700 BC, followed by mung, soy and azuki beans. Rice was also independently domesticated in West Africa and cultivated by 1000 BC.[8][9] Pigs were domesticated in Mesopotamia around 11,000 years ago, followed by sheep. Cattle were domesticated from the wild aurochs in the areas of modern Turkey and India around 8500 BC. Camels were domesticated late, perhaps around 3000 BC.

In subsaharan Africa, sorghum was domesticated in the Sahel region of Africa by 3000 BC, along with pearl millet by 2000 BC.[10][11] Yams were domesticated in several distinct locations, including West Africa (unknown date), and cowpeas by 2500 BC.[12][13] Rice (African rice) was also independently domesticated in West Africa and cultivated by 1000 BC.[8][9] Teff and likely finger millet were domesticated in Ethiopia by 3000 BC, along with noog, ensete, and coffee.[14][15] Other plant foods domesticated in Africa include watermelon, okra, tamarind and black eyed peas, along with tree crops such as the kola nut and oil palm.[16] Plantains were cultivated in Africa by 3000 BC and bananas by 1500 BC.[17][18] The helmeted guineafowl was domesticated in West Africa.[19] Sanga cattle was likely also domesticated in North-East Africa, around 7000 BC, and later crossbred with other species.[20][21]

In South America, agriculture began as early as 9000 BC, starting with the cultivation of several species of plants that later became only minor crops. In the Andes of South America, the potato was domesticated between 8000 BC and 5000 BC, along with beans, squash, tomatoes, peanuts, coca, llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs. Cassava was domesticated in the Amazon Basin no later than 7000 BC. Maize (Zea mays) found its way to South America from Mesoamerica, where wild teosinte was domesticated about 7000 BC and selectively bred to become domestic maize. Cotton was domesticated in Peru by 4200 BC; another species of cotton was domesticated in Mesoamerica and became by far the most important species of cotton in the textile industry in modern times.[22] Evidence of agriculture in the Eastern United States dates to about 3000 BCE. Several plants were cultivated, later to be replaced by the Three Sisters cultivation of maize, squash, and beans.

Sugarcane and some root vegetables were domesticated in New Guinea around 7000 BC. Bananas were cultivated and hybridized in the same period in Papua New Guinea. In Australia, agriculture was invented at a currently unspecified period, with the oldest eel traps of Budj Bim dating to 6,600 BC[23] and the deployment of several crops ranging from yams[24] to bananas.[25]

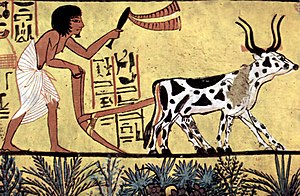

The Bronze Age, from c. 3300 BC, witnessed the intensification of agriculture in civilizations such as Mesopotamian Sumer, ancient Egypt, ancient Sudan, the Indus Valley civilisation of the Indian subcontinent, ancient China, and ancient Greece. From 100 BC to 1600 AD, world population continued to grow along with land use, as evidenced by the rapid increase in methane emissions from cattle and the cultivation of rice.[26] During the Iron Age and era of classical antiquity, the expansion of ancient Rome, both the Republic and then the Empire, throughout the ancient Mediterranean and Western Europe built upon existing systems of agriculture while also establishing the manorial system that became a bedrock of medieval agriculture. In the Middle Ages, both in Europe and in the Islamic world, agriculture was transformed with improved techniques and the diffusion of crop plants, including the introduction of sugar, rice, cotton and fruit trees such as the orange to Europe by way of Al-Andalus. After the voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1492, the Columbian exchange brought New World crops such as maize, potatoes, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, and manioc to Europe, and Old World crops such as wheat, barley, rice, and turnips, and livestock including horses, cattle, sheep, and goats to the Americas.

Irrigation, crop rotation, and fertilizers were introduced soon after the Neolithic Revolution and developed much further in the past 200 years, starting with the British Agricultural Revolution. Since 1900, agriculture in the developed nations, and to a lesser extent in the developing world, has seen large rises in productivity as human labour has been replaced by mechanization, and assisted by synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and selective breeding. The Haber-Bosch process allowed the synthesis of ammonium nitrate fertilizer on an industrial scale, greatly increasing crop yields. Modern agriculture has raised social, political, and environmental issues including overpopulation, water pollution, biofuels, genetically modified organisms, tariffs and farm subsidies. In response, organic farming developed in the twentieth century as an alternative to the use of synthetic pesticides.

- ^ "The Development of Agriculture". National Geographic. 2022-07-08. Archived from the original on 2023-01-30. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Snir, Ainit (2015). "The Origin of Cultivation and Proto-Weeds, Long before Neolithic Farming". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0131422. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1031422S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131422. PMC 4511808. PMID 26200895.

- ^ Zeder, Melinda (October 2011). "The Origins of Agriculture in the Near East". Current Anthropology. 52 (S4): 221–235. doi:10.1086/659307. JSTOR 10.1086/659307. S2CID 8202907.

- ^ Hirst, Kris (June 2019). "Domestication History of Rye". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Seabra, Luís; Teira-Brión, Andrés; López-Dóriga, Inés; Martín-Seijo, María; Almeida, Rubim; Tereso, João Pedro (10 May 2023). "The introduction and spread of rye (Secale cereale) in the Iberian Peninsula". PLOS ONE. 18 (5): e0284222. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1884222S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0284222. PMC 10171662. PMID 37163473.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pnas1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Choi, Jae Young; Zaidem, Maricris; Gutaker, Rafal; Dorph, Katherine; Singh, Rakesh Kumar; Purugganan, Michael D. (2019-03-07). "The complex geography of domestication of the African rice Oryza glaberrima". PLOS Genetics. 15 (3): e1007414. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007414. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 6424484. PMID 30845217.

- ^ a b Cubry, Philippe; Tranchant-Dubreuil, Christine; Thuillet, Anne-Céline; Monat, Cécile; Ndjiondjop, Marie-Noelle; Labadie, Karine; Cruaud, Corinne; Engelen, Stefan; Scarcelli, Nora; Rhoné, Bénédicte; Burgarella, Concetta (2018-07-23). "The Rise and Fall of African Rice Cultivation Revealed by Analysis of 246 New Genomes". Current Biology. 28 (14): 2274–2282.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.066. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 29983312. S2CID 51600014.

- ^ Winchell, Frank; Brass, Michael; Manzo, Andrea; Beldados, Alemseged; Perna, Valentina; Murphy, Charlene; Stevens, Chris; Fuller, Dorian Q. (2018). "On the Origins and Dissemination of Domesticated Sorghum and Pearl Millet across Africa and into India: a View from the Butana Group of the Far Eastern Sahel". The African Archaeological Review. 35 (4): 483–505. doi:10.1007/s10437-018-9314-2. ISSN 0263-0338. PMC 6394749. PMID 30880862.

- ^ Manning, Katie; Pelling, Ruth; Higham, Tom; Schwenniger, Jean-Luc; Fuller, Dorian Q. (2011-02-01). "4500-Year old domesticated pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) from the Tilemsi Valley, Mali: new insights into an alternative cereal domestication pathway". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (2): 312–322. Bibcode:2011JArSc..38..312M. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.09.007. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Scarcelli, Nora; Cubry, Philippe; Akakpo, Roland; Thuillet, Anne-Céline; Obidiegwu, Jude; Baco, Mohamed N.; Otoo, Emmanuel; Sonké, Bonaventure; Dansi, Alexandre; Djedatin, Gustave; Mariac, Cédric (2019-05-03). "Yam genomics supports West Africa as a major cradle of crop domestication". Science Advances. 5 (5): eaaw1947. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.1947S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw1947. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6527260. PMID 31114806.

- ^ Herniter, Ira A.; Muñoz-Amatriaín, María; Close, Timothy J. (December 2020). "Genetic, textual, and archeological evidence of the historical global spread of cowpea ( Vigna unguiculata [L.] Walp.)". Legume Science. 2 (4). doi:10.1002/leg3.57. ISSN 2639-6181. S2CID 220516241.

- ^ Edward, Sue B. (1991), Hawkes, J. G.; Engels, J. M. M.; Worede, M. (eds.), "Crops with wild relatives found in Ethiopia", Plant Genetic Resources of Ethiopia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 42–74, ISBN 978-0-521-38456-8, retrieved 2022-08-09

- ^ "Finger Millet". Crop Wild Relatives. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Plant studies show where Africa's early farmers tamed some of the continent's key crops". science.org. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Why It's Difficult to Chart Banana History". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2022-08-11.

- ^ "Early Africans Went Bananas". science.org. Retrieved 2022-08-11.

- ^ Shen, Quan-Kuan; Peng, Min-Sheng; Adeola, Adeniyi C; Kui, Ling; et al. (8 June 2021). "Genomic Analyses Unveil Helmeted Guinea Fowl ( Numida meleagris ) Domestication in West Africa". Genome Biology and Evolution. 13 (6). doi:10.1093/gbe/evab090. PMC 8214406. PMID 34009300.

- ^ Pitt, Daniel; Sevane, Natalia; Nicolazzi, Ezequiel L.; MacHugh, David E.; Park, Stephen D. E.; Colli, Licia; Martinez, Rodrigo; Bruford, Michael W.; Orozco-terWengel, Pablo (January 2019). "Domestication of cattle: Two or three events?". Evolutionary Applications. 12 (1): 123–136. Bibcode:2019EvApp..12..123P. doi:10.1111/eva.12674. ISSN 1752-4571. PMC 6304694. PMID 30622640.

- ^ Mwai, Okeyo; Hanotte, Olivier; Kwon, Young-Jun; Cho, Seoae (2015-06-11). "- Invited Review - African Indigenous Cattle: Unique Genetic Resources in a Rapidly Changing World". Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 28 (7): 911–921. doi:10.5713/ajas.15.0002R. ISSN 1011-2367. PMC 4478499. PMID 26104394.

- ^ World Cotton Production, Yara North America

- ^ National Heritage Places – Budj Bim National Heritage Landscape". Australian Government. Dept of the Environment and Energy. 20 July 2004. Retrieved 30 January 2020. See also attached documents: National Heritage List Location and Boundary Map, and Government Gazette, 20 July 2004.

- ^ Gammage, Bill (October 2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. pp. 281–304. ISBN 978-1-74237-748-3.

- ^ "Indigenous Australians 'farmed bananas 2,000 years ago'". BBC News. 12 August 2020.

- ^ Stromberg, Joseph (February 2013). "Classical gas". Smithsonian. 43 (10): 18. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.