Back جمعية الأصدقاء الدينية Arabic الكويكرز ARZ Sociedá Relixosa de los Amigos AST Квакеры Byelorussian Квакеры BE-X-OLD Квакери Bulgarian Kevredigezh relijius ar Vignoned Breton Kvekeri BS Societat Religiosa d'Amics Catalan Kvakeři Czech

| Religious Society of Friends | |

|---|---|

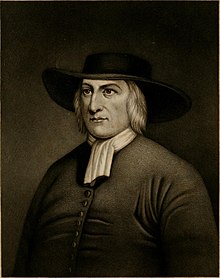

George Fox, the principal early leader of the Quakers | |

| Theology | Variable; depends on meeting |

| Polity | Congregational |

| Distinct fellowships | Friends World Committee for Consultation |

| Associations | Britain Yearly Meeting, Friends United Meeting, Evangelical Friends Church International, Central Yearly Meeting of Friends, Conservative Friends, Friends General Conference, Beanite Quakerism |

| Founder | George Fox Margaret Fell |

| Origin | Mid-17th century England |

| Separated from | Church of England |

| Separations | Shakers[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Quakerism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members of these movements ("the Friends") are generally united by a belief in each human's ability to experience the light within or "answering that of God in every one".[2] Some profess a priesthood of all believers inspired by the First Epistle of Peter.[3][4][5][6] They include those with evangelical, holiness, liberal, and traditional Quaker understandings of Christianity. There are also Nontheist Quakers, whose spiritual practice does not rely on the existence of God. To differing extents, the Friends avoid creeds and hierarchical structures.[7] In 2017, there were an estimated 377,557 adult Quakers, 49% of them in Africa.[8]

Some 89% of Quakers worldwide belong to evangelical and programmed branches[9] that hold services with singing and a prepared Bible message coordinated by a pastor. Some 11% practice waiting worship or unprogrammed worship (commonly Meeting for Worship),[10] where the unplanned order of service is mainly silent and may include unprepared vocal ministry from those present. Some meetings of both types have Recorded Ministers present, Friends recognised for their gift of vocal ministry.[11]

The proto-evangelical Christian movement dubbed Quakerism arose in mid-17th-century England from the Legatine-Arians and other dissenting Protestant groups breaking with the established Church of England.[12] The Quakers, especially the Valiant Sixty, sought to convert others by travelling through Britain and overseas preaching the Gospel. Some early Quaker ministers were women.[13] They based their message on a belief that "Christ has come to teach his people himself", stressing direct relations with God through Jesus Christ and belief in the universal priesthood of all believers.[14] This personal religious experience of Christ was acquired by direct experience and by reading and studying the Bible.[15] Quakers focused their private lives on behaviour and speech reflecting emotional purity and the light of God, with a goal of Christian perfection.[16][17]

Past Quakers were known to use thee as an ordinary pronoun, refuse to participate in war, wear plain dress, refuse to swear oaths, oppose slavery, and practice teetotalism.[18] Some Quakers founded banks and financial institutions, including Barclays, Lloyds, and Friends Provident; manufacturers including the footwear firm of C. & J. Clark and the big three British confectionery makers Cadbury, Rowntree and Fry; and philanthropic efforts, including abolition of slavery, prison reform, and social justice.[19] In 1947, in recognition of their dedication to peace and the common good, Quakers represented by the British Friends Service Council and the American Friends Service Committee were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[20][21]

- ^ Michael Bjerknes Aune; Valerie M. DeMarinis (1996). Religious and Social Ritual: Interdisciplinary Explorations. SUNY Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7914-2825-2.

- ^ Fox, George (1903). George Fox's Journal. Isbister and Company Limited. pp. 215–216.

This is the word of the Lord God to you all, and a charge to you all in the presence of the living God; be patterns, be examples in all your countries, places, islands, nations, wherever you come; that your carriage and life may preach among all sorts of people and to them: then you will come to walk cheerfully over the world, answering that of God in every one; whereby in them ye may be a blessing, and make the witness of God in them to bless you: then to the Lord God you will be a sweet savour, and a blessing.

- ^ "Membership | Quaker faith & practice". qfp.quaker.org.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Baltimore Yearly Meeting Faith & Practice". August 2011. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012.

- ^ 1 Peter 2:9

- ^ "'That of God' in every person". Quakers in Belgium and Luxembourg.

- ^ Fager, Chuck. "The Trouble With 'Ministers'". quakertheology.org. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Finding Quakers Around the World" (PDF). Friends World Committee for Consultation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain (2012). Epistles and Testimonies (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2016.

- ^ Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain (2012). Epistles and Testimonies (PDF). p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2015. [dead link]

- ^ Drayton, Brian (23 December 1994). "FGC Library: Recorded Ministers in the Society of Friends, Then and Now". Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Christian Scholar's Review, Volume 27. Hope College. 1997. p. 205.

This was especially true of proto-evangelical movements like the Quakers, organized as the Religious Society of Friends by George Fox in 1668 as a group of Christians who rejected clerical authority and taught that the Holy Spirit guided

- ^ Bacon, Margaret (1986). Mothers of Feminism: The Story of Quaker Women in America. San Francisco: Harper & Row. p. 24.

- ^ Fox, George (1803). Armistead, Wilson (ed.). Journal of George Fox. Vol. 2 (7 ed.). p. 186.

- ^ World Council of Churches. "Friends (Quakers)". Church Families. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011.

- ^ Stewart, Kathleen Anne (1992). The York Retreat in the Light of the Quaker Way: Moral Treatment Theory : Humane Therapy Or Mind Control?. William Sessions. ISBN 9781850720898.

On the other hand, Fox believed that perfectionism and freedom from sin were possible in this world.

- ^ Levy, Barry (30 June 1988). Quakers and the American Family: British Settlement in the Delaware Valley. Oxford University Press, US. pp. 128. ISBN 9780198021674.

- ^ "Society of Friends | religion". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (20 January 2010). "How did Quakers conquer the British sweet shop?". BBC News. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Jahn, Gunnar. "Award Ceremony Speech (1947)". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Abrams, Irwin (1991). "The Quaker Peace Testimony and the Nobel Peace Prize". Retrieved 24 November 2018.