Raj Chetty... ha[s] pieced together an astonishing series of findings: that absolute mobility (the chance that a child will go on to earn more than their parents) has dropped from 90%, a near certainty, to 50%, a coin-toss; that the gap in life-expectancy between rich and poor has widened even as that between blacks and whites has narrowed; and that although the chances of upward mobility differ greatly from one neighbourhood to the next, in nearly every part of America the path for black boys is steeper.

—The Economist, 2020[1]

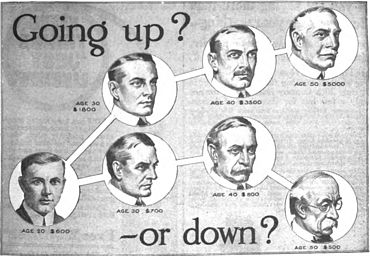

Socioeconomic mobility in the United States refers to the upward or downward movement of Americans from one social class or economic level to another,[2] through job changes, inheritance, marriage, connections, tax changes, innovation, illegal activities, hard work, lobbying, luck, health changes or other factors.

This mobility can be the change in socioeconomic status between parents and children ("inter-generational"); or over the course of a person's lifetime ("intra-generational"). Socioeconomic mobility typically refers to "relative mobility", the chance that an individual American's income or social status will rise or fall in comparison to other Americans, but can also refer to "absolute" mobility, based on changes in living standards in America.[3]

Several studies have found that inter-generational mobility is lower in the US than in some European countries, in particular the Nordic countries.[4][5] The US ranked 27th in the world in the 2020 Global Social Mobility Index.[6]

Social mobility in the US has either remained unchanged or decreased since the 1970s.[7][8][9][10][11] A 2008 study showed that economic mobility in the U.S. increased from 1950 to 1980, but has declined sharply since 1980.[12] A 2012 study conducted by the Pew Charitable Trusts found that the bottom quintile is 57% likely to experience upward mobility and only 7% to experience downward mobility.[13] A 2013 Brookings Institution study found income inequality was increasing and becoming more permanent, sharply reducing social mobility.[14] A large academic study released in 2014 found US mobility overall has not changed appreciably in the last 25 years (for children born between 1971 and 1996), but a variety of up and down mobility changes were found in several different parts of the country. On average, American children entering the labor market today have the same chances of moving up in the income distribution (relative to their parents) as children born in the 1970s.[15][16]

- ^ "Two Leading Economists Disagree About the Flagging American Dream". The Economist. May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Random House Unabridged Dictionary second edition.

- ^ "Glossary" (PDF). Polity. Archived from the original on October 29, 2005. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Harder for Americans to Rise From Lower Rungs | By JASON DePARLE | January 4, 2012]

- ^ Corak, Miles (May 2016). "Inequality from Generation to Generation: The United States in Comparison" (PDF). IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

- ^ "The Global Social Mobility Report 2020" (PDF). World Economic Forum. January 2020.

- ^ Chetty, Raj; Hendren, Nathaniel; Kline, Patrick; Saez, Emmanuel; Turner, Nicholas (May 1, 2014). "Is the United States Still a Land of Opportunity? Recent Trends in Intergenerational Mobility". American Economic Review. 104 (5): 141–147. doi:10.1257/aer.104.5.141. ISSN 0002-8282. S2CID 14776623.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

economistwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hungerford, Thomas L. (December 29, 2011). Changes in the distribution of income among tax filers between 1996 and 2006: The role of labor income, capital income, and tax policy (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- ^ Hungerford, Thomas L. (March 2011). "How income mobility affects income inequality: US evidence in the 1980s and the 1990s". Journal of Income Distribution. 16 (2). Ad Libros Publications Inc. in association with York University, Canada: 83–103. Pdf.

- ^ Bradbury, Katherine (October 20, 2011). Trends in U.S. family income mobility, 1969–2006 (working paper no. 11-10. Boston, Mass: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Pdf.

- ^ Aaronson, Daniel; Mazumder, Bhashkar (Winter 2008). "Intergenerational economic mobility in the United States, 1940 to 2000". The Journal of Human Resources. 43 (1). The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee: 139–72. doi:10.1353/jhr.2008.0008. S2CID 55711878.Pdf.

- ^ Urahn, Susan K., et al. (July 2012) Pursuing the American Dream: Economic Mobility Across Generations Pew Charitable Trusts

- ^ Vasia Panousi; Ivan Vidangos; Shanti Ramnath; Jason DeBacker; Bradley Heim (Spring 2013). "Inequality Rising and Permanent Over Past Two Decades". Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ LEONHARDT, DAVID (January 23, 2014). "Upward Mobility Has Not Declined, Study Says". New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ Chetty, Raj; Nathaniel Henderson; Patrick Kline; Emmanuel Saez; Nicholas Turner. "NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES, WHERE IS THE LAND OF OPPORTUNITY? THE GEOGRAPHY OF INTERGENERATIONAL MOBILITY IN THE UNITED STATES". January 2014. Equality of Opportunity Project. Retrieved January 23, 2014.