Back تمرد الويسكي Arabic ویسکی عوصیانی AZB Паўстанне з-за віскі Byelorussian Whisková rebelie Czech Whiskey-Rebellion German Viskia Ribelo Esperanto Rebelión del whiskey Spanish شورش ویسکی Persian Viskikapina Finnish Révolte du Whisky French

| Whiskey Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

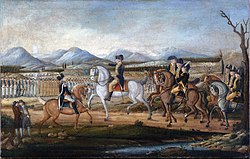

George Washington reviews the troops near Fort Cumberland, Maryland, before their march to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Frontier tax protesters | United States government | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| James McFarlane † |

George Washington Alexander Hamilton Henry Lee III Thomas Sim Lee | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Rebels | State militia from: | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 600 Pennsylvania rebels |

13,000 Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey and Pennsylvania militia 10 regular army troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3–4 killed 170 captured[1] | None; About 12 died from illness or in accidents[2] | ||||||

| 2 civilian casualties | |||||||

The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax imposed on a domestic product by the newly formed federal government. Beer was difficult to transport and spoiled more easily than rum and whiskey. Rum distillation in the United States had been disrupted during the American Revolutionary War, and whiskey distribution and consumption increased afterwards (aggregate production had not surpassed rum by 1791). The "whiskey tax" became law in 1791, and was intended to generate revenue to pay the war debt incurred during the Revolutionary War. The tax applied to all distilled spirits, but consumption of American whiskey was rapidly expanding in the late 18th century, so the excise became widely known as a "whiskey tax".[3] Farmers of the western frontier were accustomed to distilling their surplus rye, barley, wheat, corn, or fermented grain mixtures to make whiskey. These farmers resisted the tax. In these regions, whiskey often served as a medium of exchange. Many of the resisters were war veterans who believed that they were fighting for the principles of the American Revolution, in particular against taxation without local representation, while the federal government maintained that the taxes were the legal expression of Congressional taxation powers.

Throughout Western Pennsylvania counties, protesters used violence and intimidation to prevent federal officials from collecting the tax. Resistance came to a climax in July 1794, when a US marshal arrived in western Pennsylvania to serve writs to distillers who had not paid the excise. The alarm was raised, and more than 500 armed men attacked the fortified home of tax inspector John Neville. Washington responded by sending peace commissioners to western Pennsylvania to negotiate with the rebels, while at the same time calling on governors to send a militia force to enforce the tax. Washington himself rode at the head of an army to suppress the insurgency, with 13,000 militiamen provided by the governors of Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The rebels all went home before the arrival of the army, and there was no confrontation. About 20 men were arrested, but all were later acquitted or pardoned. Most distillers in nearby Kentucky were found to be all but impossible to tax—in the next six years, over 175 distillers from Kentucky were convicted of violating the tax law.[4] Numerous examples of resistance are recorded in court documents and newspaper accounts.[5]

The Whiskey Rebellion demonstrated that the new national government had the will and ability to suppress violent resistance to its laws, though the whiskey excise remained difficult to collect. The events contributed to the formation of political parties in the United States, a process already under way. The whiskey tax was repealed in the early 1800s during the Jefferson administration. Historian Carol Berkin argues that the episode, in the long run, strengthened US nationalism because the people appreciated how well Washington handled the rebels without resorting to tyranny.[6]

- ^ Slaughter 1986, pp. 210–14, 219.

- ^ Robert W. Coakley, The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1789–1878 (DIANE Publishing, 1996), 67.

- ^ Risen, Clay (December 6, 2013). "How America Learned to Love Whiskey". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ Rorabaugh, W. J. (1979). The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. Oxford University Press. p. 53.

- ^ Howlett, Leon (2012). The Kentucky Bourbon Experience: A Visual Tour of Kentucky's Bourbon Distilleries. p. 7.

- ^ Carol Berkin (2017). A Sovereign People: The Crises of the 1790s and the Birth of American Nationalism. pp. 7–80.