Back Huainanzi Catalan Huainanzi German Huainanzi Spanish Huainanzi French Huaj-nan-ce Hungarian Huainanzi ID Huainanzi Italian 淮南子 Japanese 회남자 Korean Huainanzi Dutch

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (February 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Huainanzi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Qing-era copy of Huainanzi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 淮南子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | [The Writings of] the Huainan Masters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

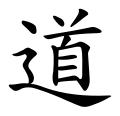

| Taoism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Confucianism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

The Huainanzi is an ancient Chinese text made up of essays from scholarly debates held at the court of Liu An, Prince of Huainan, before 139 BCE. Compiled as a handbook for an enlightened sovereign and his court, the work attempts to define the conditions for a perfect socio-political order, derived mainly from a perfect ruler.[1] With a notable Zhuangzi 'Taoist' influence, including Chinese folk theories of yin and yang and Wu Xing, the Huainanzi draws on Taoist, Legalist, Confucian, and Mohist concepts, but subverts the latter three in favor of a less active ruler, as prominent in the early Han dynasty before the Emperor Wu.[2]

The early Han authors of the Huainanzi likely did not yet call themselves Taoist, and differ from Taoism as later understood.[3] But K.C. Hsiao and the work's modern translators still considered it a 'principle' example of Han 'Taoism', retrospectively.[4] Although the Confucians classified the text as Syncretist (Zajia), its ideas theoretically contributed to the later founding of the Taoist church in 184 c.e.[5] Sima Tan may have even had the "subversive 'syncretism'" of the Huainanzi in mind when he coined the term, claiming to "pick what is good among the Confucians and Mohists."[6]

- ^ Le Blanc (1993), p. 189.

- ^ Goldin 2005a, p. 104; Creel 1970, p. 101.

- ^ Goldin 2005a, p. 91.

- ^ Liu 2014, p. 100.

- ^ Meyer 2012, p. 55.

- ^ Goldin 2005a, p. 111.