Back تحليل نمط بقع الدم Arabic Qan ləkəsi analizi Azerbaijani Blutspurenmusteranalyse German تحلیل آثار خون Persian Morphoanalyse des traces de sang French रक्त-दाग के प्रतिमान की जांच Hindi Analisi delle tracce ematiche Italian Bloedspatpatroononderzoek Dutch د وینو داغ اثارو تحلیل Pashto/Pushto Анализ брызг крови Russian

| Part of a series on |

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

Bloodstain pattern analysis (BPA) is a forensic discipline focused on analyzing bloodstains left at known, or suspected crime scenes through visual pattern recognition and physics-based assessments. This is done with the purpose of drawing inferences about the nature, timing and other details of the crime.[1] At its core, BPA revolves around recognizing and categorizing bloodstain patterns, a task essential for reconstructing events in crimes or accidents, verifying statements made during investigations, resolving uncertainties about involvement in a crime, identifying areas with a high likelihood of offender movement for prioritized DNA sampling, and discerning between homicides, suicides, and accidents.[2]

Since the late 1950s, BPA experts have claimed to be able to use biology, physics (fluid dynamics), and mathematical calculations to reconstruct with accuracy events at a crime scene, and these claims have been accepted by the criminal justice system in the US.[3]

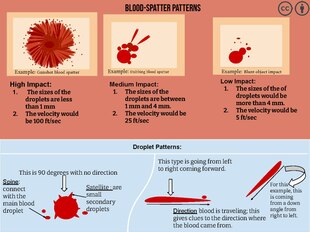

Grounded in principles of physics, biology, chemistry, and medicine, bloodstain pattern analysts use a variety of different classification methods. The most common classification method was created by S. James, P. Kish, and P. Sutton,[4] and it divides bloodstains into three categories: passive, spatter, and altered.

Despite its importance, classifying bloodstain patterns poses challenges due to the absence of a universally accepted methodology and the natural uncertainty in interpreting such patterns. Current classification methods often describe pattern types based on their formation mechanisms rather than observable characteristics, complicating the analysis process.[5] Ideally, BPA involves meticulous evaluation of pattern characteristics against objective criteria, followed by interpretation to aid crime scene reconstruction.[5] However, the lack of discipline standards in methodology underscores the need for consistency and rigor in BPA practices.

Efforts by organizations like the Organization of Scientific Area Committees (OSAC) BPA Subcommittee aim to establish standards for training, terminology, quality assurance, and procedure validation within the discipline.[6]

The validity of bloodstain pattern analysis has been questioned since the 1990s, and more recent studies cast significant doubt on its accuracy.[7] A comprehensive 2009 National Academy of Sciences report concluded that "the uncertainties associated with bloodstain pattern analysis are enormous" and that purported bloodstain pattern experts' opinions are "more subjective than scientific."[8][7] The report highlighted several incidents of blood spatter analysts overstating their qualifications and questioned the reliability of their methods.[8][9] In 2021, the largest-to-date study on the accuracy of BPA was published, with results "show[ing] that [BPA conclusions] were often erroneous and often contradicted other analysts."[10]

- ^ A Simplified Guide To Bloodstain Pattern Analysis, The National Forensic Science Technology Center (NFSTC), Florida International University

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:3was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ James, Stuart H.; Kish, Paul E.; Sutton, T. Paulette (2005). Principles of Bloodstain Pattern Analysis: Theory and Practice. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-3946-7.

- ^ Brodbeck, Silke (2012). "Introduction to Bloodstain Pattern Analysis". SIAK-Journal − Journal for Police Science and Practice. 2: 51–57. doi:10.7396/IE_2012_E. ISSN 1813-3495.

- ^ a b Arthur, Ravishka M.; Cockerton, Sarah L.; de Bruin, Karla G.; Taylor, Michael C. (2015). "A novel, element-based approach for the objective classification of bloodstain patterns". Forensic Science International. 257: 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.08.028. PMID 26386338.

- ^ Taylor, Michael C.; Laber, Terry L.; Kish, Paul E.; Owens, Glynn; Osborne, Nikola K. P. (2016). "The Reliability of Pattern Classification in Bloodstain Pattern Analysis, Part 1: Bloodstain Patterns on Rigid Non-absorbent Surfaces". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 61 (4): 922–927. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.13091. ISSN 0022-1198. PMID 27102227.

- ^ a b Smith, Leora (13 December 2018). "How a Dubious Forensic Science Spread Like a Virus". ProPublica. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ a b National Research Council. Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009. Archived

- ^ Moore, Solomon (February 4, 2009). "Science found wanting in nation's crime labs". New York Times.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Hicklin et alwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).