Back صدام الحضارات Arabic صدام الحضارات ARZ Sivilizasiyaların toqquşması Azerbaijani مدنیتلر چاتیشماسی AZB Сутыкненне цывілізацый Byelorussian Сблъсъкът на цивилизациите и преобразуването на световния ред Bulgarian Xoc de civilitzacions Catalan The Clash of Civilizations CEB پێکدادانی شارستانیەتەکان CKB Střet civilizací Czech

| |

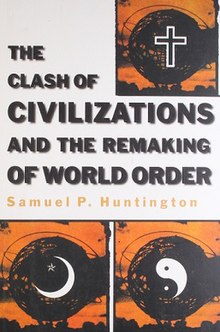

| Author | Samuel P. Huntington |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster |

Publication date | 1996 |

| Publication place | United States |

| ISBN | 978-0-684-84441-1 |

The "Clash of Civilizations" is a thesis that people's cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post–Cold War world.[1][2][3][4][5] The American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington argued that future wars would be fought not between countries, but between cultures.[1][6] It was proposed in a 1992 lecture at the American Enterprise Institute, which was then developed in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article titled "The Clash of Civilizations?",[7] in response to his former student Francis Fukuyama's 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington later expanded his thesis in a 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.[8]

The phrase itself was earlier used by Albert Camus in 1946,[9] by Girilal Jain in his analysis of the Ayodhya dispute in 1988,[10][11] by Bernard Lewis in an article in the September 1990 issue of The Atlantic Monthly titled "The Roots of Muslim Rage"[12] and by Mahdi El Mandjra in his book "La première guerre civilisationnelle" published in 1992.[13][14] Even earlier, the phrase appears in a 1926 book regarding the Middle East by Basil Mathews: Young Islam on Trek: A Study in the Clash of Civilizations. This expression derives from "clash of cultures", already used during the colonial period and the Belle Époque.[15]

Huntington began his thinking by surveying the diverse theories about the nature of global politics in the post–Cold War period. Some theorists and writers argued that human rights, liberal democracy, and the capitalist free market economy had become the only remaining ideological alternative for nations in the post–Cold War world. Specifically, Francis Fukuyama argued that the world had reached the 'end of history' in a Hegelian sense.

Huntington believed that while the age of ideology had ended, the world had only reverted to a normal state of affairs characterized by cultural conflict. In his thesis, he argued that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural lines.[16] As an extension, he posits that the concept of different civilizations, as the highest category of cultural identity, will become increasingly useful in analyzing the potential for conflict. At the end of his 1993 Foreign Affairs article, "The Clash of Civilizations?", Huntington writes, "This is not to advocate the desirability of conflicts between civilizations. It is to set forth descriptive hypothesis as to what the future may be like."[7]

In addition, the clash of civilizations, for Huntington, represents a development of history. In the past, world history was mainly about the struggles between monarchs, nations and ideologies, such as that seen within Western civilization. However, after the end of the Cold War, world politics moved into a new phase, in which non-Western civilizations are no longer the exploited recipients of Western civilization but have become additional important actors joining the West to shape and move world history.[17]

- ^ a b Huntington, Samuel P. (1993). "The Clash of Civilizations?". Foreign Affairs. 72 (3): 22–49. doi:10.2307/20045621. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 20045621.

- ^ "gbse.com.my" (PDF). gbse.com.my. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ Emily, Stacey (October 29, 2021). Contemporary Politics and Social Movements in an Isolated World: Emerging Research and Opportunities: Emerging Research and Opportunities. IGI Global. ISBN 978-1-7998-7616-8.

- ^ Eriksen, Thomas Hylland; Garsten, Christina; Randeria, Shalini (October 1, 2014). Anthropology Now and Next: Essays in Honor of Ulf Hannerz. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78238-450-2.

- ^ Krieger, Douglas W. (November 22, 2014). The Two Witnesses. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-312-67075-4.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Haynes, Jeffrey (May 11, 2021). A Quarter Century of the "Clash of Civilizations". Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-38383-6.

- ^ a b Official copy (free preview): The Clash of Civilizations?, Foreign Affairs, Summer 1993

- ^ "WashingtonPost.com: The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order". The Washington Post.

- ^

"Page non trouvée | INA". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.le problème russo-américain, et là nous revenons à l'Algérie, va être dépassé lui-même avant très peu, cela ne sera pas un choc d'empires nous assistons au choc de civilisations et nous voyons dans le monde entier les civilisations colonisées surgir peu à peu et se dresser contre les civilisations colonisatrices.

- ^ Elst, Koenraad. ""Some recollections from my acquaintance with Sita Ram Goel", ch.6 of K. Elst, ed.: India's Only Communalist, In Commemoration of Sita Ram Goel". Retrieved October 23, 2022 – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ Elst, K. India's Only Communalist: an Introduction to the Work of Sita Ram Goel, in Sharma, A. (2001). Hinduism and secularism: After Ayodhya. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- ^ Bernard Lewis: The Roots of Muslim Rage The Atlantic Monthly, September 1990

- ^ Elmandjra, Mahdi (1992). Première guerre civilisationnelle (in French). Toubkal.

- ^ Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations (1996), p. 246: " 'La premiere guerre civilisationnelle' the distinguished Moroccan scholar Mahdi Elmandjra called the Gulf War as it was being fought."

- ^ Louis Massignon, La psychologie musulmane (1931), in Idem, Ecrits mémorables, t. I, Paris, Robert Laffont, 2009, p. 629: "Après la venue de Bonaparte au Caire, le clash of cultures entre l'ancienne Chrétienté et l'Islam prit un nouvel aspect, par invasion (sans échange) de l'échelle de valeurs occidentales dans la mentalité collective musulmane."

- ^ mehbaliyev (October 30, 2010). "Civilizations, their nature and clash possibilities (c) Rashad Mehbal..."

- ^ Murden S. Cultures in world affairs. In: Baylis J, Smith S, Owens P, editors. The Globalization of World Politics. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. p. 416-426.