Back የአሾካ አዋጆች Amharic مراسيم أشوكا Arabic অশোকৰ অনুশাসন Assamese अशोक के आदेशलेख Bihari অশোক শিলালিপি Bengali/Bangla Edictes d'Aixoka Catalan Ašókovy edikty Czech Ashoka-Edikte German Έδικτα του Ασόκα Greek Edictos de Ashoka Spanish

| Edicts of Ashoka | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Rocks, pillars, stone slabs |

| Created | 3rd century BCE |

| Present location | Nepal, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh |

| Part of a series on the |

| Edicts of Ashoka |

|---|

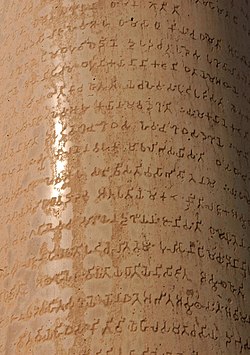

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who ruled most of the Indian subcontinent from 268 BCE to 232 BCE.[1] Ashoka used the expression Dhaṃma Lipi (Prakrit in the Brahmi script: 𑀥𑀁𑀫𑀮𑀺𑀧𑀺, "Inscriptions of the Dharma") to describe his own Edicts.[2] These inscriptions were dispersed throughout the areas of modern-day India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and provide the first tangible evidence of Buddhism. The edicts describe in detail Ashoka's policy on dhamma, an earnest attempt to solve some of the problems that a complex society faced.[3] According to the edicts, the extent of his promotion of dhamma during this period reached as far as the Greeks in the Mediterranean region. While the inscriptions mention the conversion of Ashoka to Buddhism, the dhamma that he promotes is largely ecumenical and non-sectarian in nature. As historian Romila Thapar relates:

In his edicts Aśoka defines the main principles of dhamma as non-violence, tolerance of all sects and opinions, obedience to parents, respect to brahmins and other religious teachers and priests, liberality toward friends, humane treatment of servants and generosity towards all. It suggests a general ethic of behaviour to which no religious or social group could object. It also could act as a focus of loyalty to weld together the diverse strands that made up the empire. Interestingly, the Greek versions of these edicts translate dhamma as eusebeia (piety) and no mention is made anywhere of the teachings of the Buddha, as would be expected if Aśoka had been propagating Buddhism.’[4]

The inscriptions show his efforts to develop the dhamma throughout his empire. Although Buddhism as well as Gautama Buddha are mentioned, the edicts focus on social and moral precepts rather than specific religious practices or the philosophical dimension of Buddhism. These were located in public places and were meant for people to read.

In these inscriptions, Ashoka refers to himself as "Beloved of the Gods" (Devanampiya). The identification of Devanampiya with Ashoka was confirmed by an inscription discovered in 1915 by C. Beadon, a British gold-mining engineer, at Maski, a town in Madras Presidency (present day Raichur district, Karnataka). Another minor rock edict, found at the village Gujarra in Gwalior State (present day Datia district of Madhya Pradesh), also used the name of Ashoka together with his titles: Devanampiya Piyadasi Asokaraja.[5] The inscriptions found in the central and eastern part of India were written in Magadhi Prakrit using the Brahmi script, while Prakrit using the Kharoshthi script, Greek and Aramaic were used in the northwest. These edicts were deciphered by British archaeologist and historian James Prinsep.[6]

The inscriptions revolve around a few recurring themes: Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism, the description of his efforts to spread dhamma, his moral and religious precepts, and his social and animal welfare program. The edicts were based on Ashoka's ideas on administration and behavior of people towards one another and religion.

- ^ Le 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 351. ISBN 9788131711200. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "The Ashokan rock edicts are a marvel of history". Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (1 June 2012), "The Decline of the Mauryas", Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, Oxford University Press, pp. 247–266, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198077244.003.0031, ISBN 978-0-19-807724-4, retrieved 22 January 2025

- ^ Malalasekera, Gunapala Piyasena (1990). Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. Government of Ceylon. p. 16. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 208.