Back Geskiedenis van Indië Afrikaans भारत केरऽ इतिहास ANP تاريخ الهند Arabic ভাৰতৰ ইতিহাস Assamese Historia de la India AST Hindistan tarixi Azerbaijani Һиндостан тарихы Bashkir Гісторыя Індыі Byelorussian История на Индия Bulgarian भारत के इतिहास Bihari

| History of India |

|---|

|

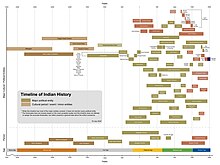

| Timeline |

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

Anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago.[1] The earliest known human remains in South Asia date to 30,000 years ago. Sedentariness began in South Asia around 7000 BCE;[2] by 4500 BCE, settled life had spread,[2] and gradually evolved into the Indus Valley Civilisation, one of three early cradles of civilisation in the Old World,[3][4] flourished between 2500 BCE and 1900 BCE in present-day Pakistan and north-western India. Early in the second millennium BCE, persistent drought caused the population of the Indus Valley to scatter from large urban centres to villages. Indo-Aryan tribes moved into the Punjab from Central Asia in several waves of migration. The Vedic Period of the Vedic people in northern India (1500–500 BCE) was marked by the composition of their extensive collections of hymns (Vedas). The social structure was loosely stratified via the varna system, incorporated into the highly evolved present-day Jāti system. The pastoral and nomadic Indo-Aryans spread from the Punjab into the Gangetic plain. Around 600 BCE, a new, interregional culture arose; then, small chieftaincies (janapadas) were consolidated into larger states (mahajanapadas). Second urbanization took place, which came with the rise of new ascetic movements and religious concepts,[5] including the rise of Jainism and Buddhism. The latter was synthesized with the preexisting religious cultures of the subcontinent, giving rise to Hinduism.

Chandragupta Maurya overthrew the Nanda Empire and established the first great empire in ancient India, the Maurya Empire. India's Mauryan king Ashoka is widely recognised for his historical acceptance of Buddhism and his attempts to spread nonviolence and peace across his empire. The Maurya Empire would collapse in 185 BCE, on the assassination of the then-emperor Brihadratha by his general Pushyamitra Shunga. Shunga would form the Shunga Empire in the north and north-east of the subcontinent, while the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom would claim the north-west and found the Indo-Greek Kingdom. Various parts of India were ruled by numerous dynasties, including the Gupta Empire, in the 4th to 6th centuries CE. This period, witnessing a Hindu religious and intellectual resurgence is known as the Classical or Golden Age of India. Aspects of Indian civilisation, administration, culture, and religion spread to much of Asia, which led to the establishment of Indianised kingdoms in the region, forming Greater India.[6][7] The most significant event between the 7th and 11th centuries was the Tripartite struggle centred on Kannauj. Southern India saw the rise of multiple imperial powers from the middle of the fifth century. The Chola dynasty conquered southern India in the 11th century. In the early medieval period, Indian mathematics, including Hindu numerals, influenced the development of mathematics and astronomy in the Arab world, including the creation of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system.[8]

Islamic conquests made limited inroads into modern Afghanistan and Sindh as early as the 8th century,[9] followed by the invasions of Mahmud Ghazni.[10] The Delhi Sultanate was founded in 1206 by Central Asian Turks who were Indianized.[11][12][13][14] They ruled a major part of the northern Indian subcontinent in the early 14th century. It was ruled by multiple Turk, Afghan and Indian dynasties, including the Turco-Mongol Indianized Tughlaq Dynasty[15] but declined in the late 14th century following the invasions of Timur[16] and saw the advent of the Malwa, Gujarat, and Bahmani Sultanates, the last of which split in 1518 into the five Deccan sultanates. The wealthy Bengal Sultanate also emerged as a major power, lasting over three centuries.[17] During this period, multiple strong Hindu kingdoms, notably the Vijayanagara Empire and the Rajput states, emerged and played significant roles in shaping the cultural and political landscape of India.

The early modern period began in the 16th century, when the Mughal Empire conquered most of the Indian subcontinent,[18] signaling the proto-industrialisation, becoming the biggest global economy and manufacturing power.[19][20][21] The Mughals suffered a gradual decline in the early 18th century, largely due to the rising power of the Marathas, who took control of extensive regions of the Indian subcontinent.[22][23] The East India Company, acting as a sovereign force on behalf of the British government, gradually acquired control of huge areas of India between the middle of the 18th and the middle of the 19th centuries. Policies of company rule in India led to the Indian Rebellion of 1857. India was afterwards ruled directly by the British Crown, in the British Raj. After World War I, a nationwide struggle for independence was launched by the Indian National Congress, led by Mahatma Gandhi. Later, the All-India Muslim League would advocate for a separate Muslim-majority nation state. The British Indian Empire was partitioned in August 1947 into the Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan, each gaining its independence.

- ^ Michael D. Petraglia; Bridget Allchin (22 May 2007). The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia: Inter-disciplinary Studies in Archaeology, Biological Anthropology, Linguistics and Genetics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4020-5562-1. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by modern humans originating in Africa. ... Coalescence dates for most non-European populations average to between 73–55 ka."

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Wright2010-p=44was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wright, Rita P. (2010). The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-57652-9.

- ^ McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-Clio. p. 387. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- ^ Flood, Gavin. Olivelle, Patrick. 2003. The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden: Blackwell. pp. 273–274

- ^ The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: From Early Times to c. 1800, Band 1 by Nicholas Tarling, p. 281

- ^ Flood, Gavin. Olivelle, Patrick. 2003. The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden: Blackwell. pp. 273–274.

- ^ Essays on Ancient India by Raj Kumar p. 199

- ^ Al Baldiah wal nahaiyah vol: 7 p. 141 "Conquest of Makran"

- ^ Meri 2005, p. 146.

- ^ Mohammad Aziz Ahmad (1939). "The Foundation of Muslim Rule in India. (1206-1290 A.D.)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 3: 832–841. JSTOR 44252438.

The government had passed from the foreign Turks to the Indian Mussalmans and their Hindu allies.

- ^ Dr. K. S. Lal (1967). History of the Khaljis, A.D. 1290-1320. p. 14.

The khalji revolt is essentially a revolt of the Indian Muslims against the Turkish hegemony, of those who looked to Delhi, against those who sought inspiration from Ghaur and Ghazna.

- ^ Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of Medieval India:From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic. p. 30. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4.

In spite of all this, capturing the throne for Khilji was a revolution, as instead of Turks, Indian Muslims gained power

- ^ John Bowman (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-231-50004-3.

- ^ Eaton, Richard Maxwell (8 March 2015). The Sufis of Bijapur, 1300-1700: Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India. Princeton University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-4008-6815-5.

- ^ Kumar, Sunil (2013). "Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526)". In Bowering, Gerhard (ed.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-0-691-13484-0.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (31 July 1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

exeterwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Parthasarathi, Prasannan (11 August 2011). Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–45. ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (25 September 2003). Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics. OECD Publishing. pp. 259–261. ISBN 9264104143.

- ^ Harrison, Lawrence E.; Berger, Peter L. (2006). Developing cultures: case studies. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-415-95279-8.

- ^ Ian Copland; Ian Mabbett; Asim Roy; et al. (2012). A History of State and Religion in India. Routledge. p. 161.

- ^ Michaud, Joseph (1926). History of Mysore Under Hyder Ali and Tippoo Sultan. p. 143.