Back لقاح معطل Arabic Vaccí inactivat Catalan Inaktivovaná vakcína Czech Totimpfstoff German Vacuna inactivada Spanish واکسن غیرفعال شده Persian Virus inactivé French 不活化ワクチン Japanese ინაქტივირებული ვაქცინა Georgian Инактивті вакцина Kazakh

| Inactivated vaccine | |

|---|---|

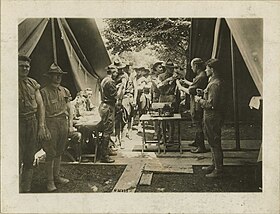

Typhoid prophylaxis for soldiers in World War I. | |

| Other names | Killed vaccine Non-replicating vaccines |

| Specialty | Public health, Immunology, Family medicine, General practice |

| Uses | prevention of infectious diseases |

| Frequency | birth to adulthood |

| Outcomes | development of active immunity in individuals; contribution to herd immunity |

An inactivated vaccine (or killed vaccine) is a type of vaccine that contains pathogens (such as virus or bacteria) that have been killed or rendered inactive, so they cannot replicate or cause disease. In contrast, live vaccines use pathogens that are still alive (but are almost always attenuated, that is, weakened). Pathogens for inactivated vaccines are grown under controlled conditions and are killed as a means to reduce infectivity and thus prevent infection from the vaccine.[1]

Inactivated vaccines were first developed in the late 1800s and early 1900s for cholera, plague, and typhoid.[2] In 1897, Japanese scientists developed an inactivated vaccine for the bubonic plague. In the 1950's, Jonas Salk created an inactivated vaccine for the poliovirus, creating the first vaccine that was both safe and effective against polio. Today, inactivated vaccines exist for many pathogens, including influenza, polio (IPV), rabies, hepatitis A, CoronaVac, Covaxin and pertussis.[3][4][5]

Because inactivated pathogens tend to produce a weaker response by the immune system than live pathogens, immunologic adjuvants and multiple "booster" injections may be required in some vaccines to provide an effective immune response against the pathogen.[1][6][7] Attenuated vaccines are often preferable for generally healthy people because a single dose is often safe and very effective. However, some people cannot take attenuated vaccines because the pathogen poses too much risk for them (for example, elderly people or people with immunodeficiency). For those patients, an inactivated vaccine can provide protection.[citation needed]

- ^ a b Petrovsky N, Aguilar JC (October 2004). "Vaccine adjuvants: current state and future trends". Immunology and Cell Biology. 82 (5): 488–496. doi:10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01272.x. PMID 15479434. S2CID 154670.

- ^ Plotkin SA, Plotkin SL (October 2011). "The development of vaccines: how the past led to the future". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 9 (12) (published 2011-10-03): 889–893. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2668. PMID 21963800. S2CID 32506969.

- ^ Wodi AP, Morelli V (2021). "Chapter 1: Principles of Vaccination" (PDF). In Hall E, Wodi AP, Hamborsky J, Morelli V, Schilllie S (eds.). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (14th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan (1997). The History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction (1st ed.). W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 1–530. ISBN 978-0-393-31611-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Hilleman, Maurice (April 1987). "Vaccines and the Eradication of Poliomyelitis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 155 (4): 509–529 – via PubMed, JSTOR, Oxford Academic, Elsevier ScienceDirect.

- ^ WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization (19 June 2019). "Influenza". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Types of Vaccines". Vaccines.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 23 July 2013. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2016.