Back الإسلام في فلسطين Arabic ফিলিস্তিনে ইসলাম Bengali/Bangla האסלאמיזציה של ארץ ישראל HE फिलिस्तीन में इस्लाम Hindi Islam di Palestina ID Islam di Palestin Malay Islam in Palestina Dutch Ислам в Государстве Палестина Russian Islam in Palestine SIMPLE Filistin'de İslam Turkish

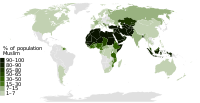

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Sunni Islam is a major religion in Palestine, being the religion of the majority of the Palestinian population. Muslims comprise 85% of the population of the West Bank, when including Israeli settlers,[1] and 99% of the population of the Gaza Strip.[2] The largest denomination among Palestinian Muslims are Sunnis, comprising 85% of the total Muslim population.

During the 7th century, the Arab Rashiduns conquered the Levant, succeeded by subsequent Arabic-speaking Muslim dynasties like the Umayyads, Abbasids and the Fatimids,[3] marking the onset of Arabization and Islamization in the region. This process involved both resettlement by nomadic tribes and individual conversions.[4][5] In the case of the Samaritans, there are records of mass conversion due to economic pressure, political instability and religious persecution in the Abbasid period.[6] Sedentarization facilitated a more rapid Islamization compared to the slower pace of individual conversions among the local populace.[4][5][7] Sufi activities[5] and changes in social structures and the weakening of local Christian authorities under Islamic rule[8] also played significant roles.

Some scholars suggest that by the arrival of the Crusaders, Palestine was already overwhelmingly Muslim,[9][10] while others claim that it was only after the Crusades that Christianity lost its majority, and that the process of mass Islamization took place much later, perhaps during the Mamluk period.[6][11]

- ^ West Bank. CIA Factbook

- ^ Gaza Strip. CIA Factbook

- ^ Gil, Moshe (1997). A History of Palestine, 634-1099. Ethel Briodo. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-59984-9. OCLC 59601193.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Ellenblum, Ronnie (2010). Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-58534-0. OCLC 958547332.

From the data given above it can be concluded that the Muslim population of Central Samaria, during the early Muslim period, was not an autochthonous population which had converted to Christianity. They arrived there either by way of migration or as a result of a process of sedentarization of the nomads who had filled the vacuum created by the departing Samaritans at the end of the Byzantine period [...] To sum up: in the only rural region in Palestine in which, according to all the written and archeological sources, the process of Islamization was completed already in the twelfth century, there occurred events consistent with the model propounded by Levtzion and Vryonis: the region was abandoned by its original sedentary population and the subsequent vacuum was apparently filled by nomads who, at a later stage, gradually became sedentarized

- ^ a b c Tramontana, Felicita (2014). Passages of Faith: Conversion in Palestinian villages (17th century) (1 ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 69, 114–115. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc16s06.10. ISBN 978-3-447-10135-6. JSTOR j.ctvc16s06.

According to Kedar, at the arrival of the Crusaders the distribution of the Muslims would therefore have varied from area to area. While some parts of Palestine were still mainly occupied by their former inhabitants, in others most of the residents were Muslim. Kedar's approach is followed by Ellenblum, who describes the spread of Islam in Palestine as the result of both resettlement by nomadic tribes and individual conversion. The coexistence of these two processes has also been described by Levtzion. Together with Speros Vryonis, who studied the importance of the process of sedentarization for the Islamization of Anatolia, Levtzion pointed out that whereas Islamization of areas due to sedentarization was a rapid process, conversely the spread of Islam among the local population through individual conversion was slow. ... Research on the topic has also highlighted the role played by Sufis and prominent local families in the spread of Islam in Palestinian villages once inhabited by Christians. This is the case for example with Dayr al-Sheykh and Sharafāt, both near to Jerusalem.

- ^ a b Levy-Rubin, Milka (2000). "New Evidence Relating to the Process of Islamization in Palestine in the Early Muslim Period: The Case of Samaria". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 43 (3): 257–276. doi:10.1163/156852000511303. ISSN 0022-4995. JSTOR 3632444.

- ^ Gideon Avni, The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach, Oxford University Press 2014 pp.312–324, 329 (theory of imported population unsubstantiated);.

- ^ Ehrlich, Michael (2022). The Islamization of the Holy Land, 634-1800. Arc Humanity Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-64189-222-3. OCLC 1310046222.

- ^ Ira M. Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, (1988) Cambridge University Press 3rd.ed.2014 p.156

- ^ Mark A. Tessler, A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Indiana University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-253-20873-4, M1 Google Print, p. 70.

- ^ Ira M. Lapidus, Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 201.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).