Back Kumbh Mela Afrikaans كومبه ميلا Arabic কুম্ভ মেলা Assamese Kumbhamela AST कुंभ मेला AWA Кумбха Мэля BE-X-OLD कुंभ मेला Bihari কুম্ভমেলা Bengali/Bangla Kumbhamela Catalan Kumbhaméla Czech

| Kumbh Mela | |

|---|---|

Nighttime view laser show, Mahakumbh 2025 Prayag Maha Kumbh Mela in 2025 | |

| Genre | Pilgrimage |

| Frequency |

|

| Location(s) | Primary Other |

| Country | India |

| Most recent | Prayag Maha Kumbh (13 January– 26 February 2025) |

| Next event | Haridwar Ardh Kumbh (March 2027)[1] Nashik-Trimbakeshwar Simhastha (July–August 2027)[2] |

| Website | kumbh |

| Kumbh Mela | |

|---|---|

| Country | India |

| Reference | 01258 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2017 (12th session) |

| List | Representative |

Unesco Cultural Heritage | |

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

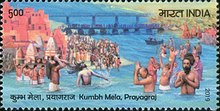

Kumbh Mela (Sanskrit: Kumbha Mēlā , pronounced [kʊˈmbʱᵊ melaː]; lit. 'festival of the Sacred Pitcher'[3]) is an important Hindu pilgrimage, celebrated approximately every 6 or 12 years, correlated with the partial or full revolution of Jupiter.[4][5]

A ritual dip in the waters marks the festival. It is also a celebration of community commerce with numerous fairs, education, religious discourses by saints, mass gatherings of monks, and entertainment.[6][7] The seekers believe that bathing in these rivers is a means to prāyaścitta (atonement, penance, restorative action) for past mistakes,[8] and that it cleanses them of their sins.[9]

In many parts of India, similar but smaller community pilgrimage and bathing festivals are called the Magha Mela, Makar Mela or equivalent. Other places where the Magha-Mela or Makar-Mela bathing pilgrimage and fairs have been called Kumbh Mela include Kurukshetra,[10][11] Rajim,[12] Mahamaham (Tamil Nadu), Sonipat,[13] and Panauti (Nepal).[14] For example, in Tamil Nadu, the Magha Mela with water-dip ritual is a festival of antiquity, and this festival is held at the Mahamaham tank (near Kaveri river) every 12 years at Kumbakonam, attracting millions of Hindus.[15][16]

Before 1858, the name "Kumbh" was applied only to the 12th occurrence of an annual mela in Haridwar during April or May. In Allahabad (now Prayagraj), there was an annual Magh Mela in January or February that had found mention in Hindu texts, including Tulsidas's Ramcharitmanas. The Haridwar mela had been riven by violence, especially by armed Akhara groups. In 1796, during East India Company rule in India, the violence in Haridwar's kumbh had taken 500 lives and a British armed unit with cannon had to be called in to stem it. In 1858, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857 had been suppressed and the British Raj instituted, Allahabad had become the capital of North-Western Provinces and Oudh. Uncertain about their place in the new political order, the Pragwals, or members of the traditional priest castes at Allahabad's sangam sought to have some latitude for their profession and proposed the idea of an organised pilgrimage with British surveillance. The British came to accept this in part because of lingering pre-1857 notions of their patronising an idealised Hinduism. The first Kumbh Mela in Allahabad was organised in 1870 with British supervision. By 1870, an adequate beginning had been made in laying a train network in India, which made travel over longer distances easier.[17]

The weeks over which the festival is observed cycle at each site approximately once every 12 years[note 1] based on the Hindu luni-solar calendar and the relative astrological positions of Jupiter, the sun and the moon. The difference between Prayag and Haridwar festivals is about 6 years, and both feature a Maha (major) and Ardha (half) Kumbh Melas. The exact years – particularly for the Kumbh Melas at Ujjain and Nashik – have been a subject of dispute in the 20th century. The Nashik and Ujjain festivals have been celebrated in the same year or one year apart,[19] typically about 3 years after the Prayagraj Kumbh Mela.[20]

The Kumbh Melas have three dates around which the significant majority of pilgrims participate, while the festival itself lasts between one[21] and three months around these dates.[22] Each festival attracts millions, with the largest gathering at the Prayag Kumbh Mela and the second largest at Haridwar.[23] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica and Indian authorities, more than 200 million Hindus gathered for the Kumbh Mela in 2019, including 50 million on the festival's most crowded day.[4] The festival is one of the largest peaceful gatherings in the world, and considered as the "world's largest congregation of religious pilgrims".[24] It has been inscribed on the UNESCO's Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[25][26] The festival is observed over many days, with the day of Amavasya attracting the largest number on a single day. According to official figures, the largest one-day attendance at the Kumbh Mela was 30 million on 10 February 2013,[27][28] and 50 million on 4 February 2019.[29][30][31]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ "हरिद्वार में 2027 के अर्द्धकुंभ को कुंभ के नाम से जाना जाएगा". Hindustan (in Hindi). 25 February 2025. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ "Maha Kumbh 2025 concludes: When is next Kumbh Mela?". Hindustan Times. 26 February 2025. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ "Kumbh Mela Hindu festival begins in India". Deutsche Welle. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ a b Kumbh Mela: Hindu festival. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2015.

The Kumbh Mela lasts several weeks and is one of the largest festivals in the world, attracting more than 200 million people in 2019, including 50 million on the festival's most auspicious day.

- ^ Haghani, Milad (14 January 2025). "The world's largest gathering: how India plans to keep 400 million pilgrims safe at the Maha Kumbh Mela festival". The Conversation. Retrieved 14 January 2025.

- ^ Diana L. Eck (2012). India: A Sacred Geography. Harmony Books. pp. 153–155. ISBN 978-0-385-53190-0.

- ^ Williams Sox (2005). Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd Edition. Vol. 8. Macmillan. pp. 5264–5265., Quote: "The special power of the Kumbha Mela is often said to be due in part to the presence of large numbers of Hindu monks, and many pilgrims seek the darsan (Skt., darsana; auspicious mutual sight) of these holy men. Others listen to religious discourses, participate in devotional singing, engage brahman priests for personal rituals, organise mass feedings of monks or the poor, or merely enjoy the spectacle. Amid this diversity of activities, the ritual bath at the conjunction of time and place is the central event of the Kumbha Mela."

- ^ Kane 1953, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Maclean, Kama (September 2009). "Seeing, Being Seen, and Not Being Seen: Pilgrimage, Tourism, and Layers of Looking at the Kumbh Mela". CrossCurrents. 59 (3): 319–341. doi:10.1111/j.1939-3881.2009.00082.x. S2CID 170879396.

- ^ General, India Office of the Registrar (14 January 1972). "Census of India, 1971: Haryana". Manager of Publications – via Google Books.

- ^ 1988, Town Survey Report: Haryana, Thanesar, District Kurukshetra, page 137-.

- ^ "Rajim Kumbh Kalp Mela 2025: यूपी के साथ-साथ अब 'छत्तीसगढ़ के प्रयागराज' में जुटेंगे संत, आज से महाशिवरात्रि तक है राजिम कुंभ". mpcg.ndtv.in (in Hindi). Retrieved 26 February 2025.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

satk1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gerard Toffin (2012). Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara (ed.). Sins and Sinners: Perspectives from Asian Religions. BRILL Academic. pp. 330 with footnote 18. ISBN 978-90-04-23200-6.

- ^ Maclean 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Diana L. Eck (2012). India: A Sacred Geography. Harmony Books. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-385-53190-0.

- ^ Maclean 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jacobsen2008p40was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Matthew James Clark (2006). The Daśanāmī-saṃnyāsīs: The Integration of Ascetic Lineages into an Order. Brill. p. 294. ISBN 978-90-04-15211-3.

- ^ K. Shadananan Nair (2004). "Mela" (PDF). Proceedings Ol'THC. UNI-SCO/1 AI IS/I Wl IA Symposium Held in Rome, December 2003. IAHS: 165. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2008). Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-134-07459-4.

- ^ James Mallinson (2016). Rachel Dwyer (ed.). Key Concepts in Modern Indian Studies. New York University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-1-4798-4869-0.

- ^ Maclean 2008, pp. 225–226.

- ^ The Maha Kumbh Mela 2001 indianembassy.org

- ^ Kumbh Mela UNESCO Intangible World Heritage official list.

- ^ Kumbh Mela on UNESCO's list of intangibl Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Economic Times, 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Over 3 crore take holy dip in Sangam on Mauni Amavasya". India Times. 10 February 2013. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016.

- ^ Rashid, Omar (11 February 2013). "Over three crore devotees take the dip at Sangam". The Hindu. Chennai.

- ^ Jha, Monica (23 June 2020). "Eyes in the sky. Indian authorities had to manage 250 million festivalgoers. So they built a high-tech surveillance ministate". Rest of World. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "Mauni Amavasya: Five crore pilgrims take holy dip at Kumbh till 5 pm", Times of India, 4 February 2019, retrieved 24 June 2020

- ^ "A record over 24 crore people visited Kumbh-2019, more than total tourists in UP in 2014–17". Hindustan Times. 21 May 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).