Back شرعوية (فلسفة صينية) Arabic شرعويه ARZ Legizm Azerbaijani Легизъм Bulgarian আইনবাদ (চীনা দর্শন) Bengali/Bangla Lezennouriezh (prederouriezh sinaat) Breton Escola de les lleis Catalan Legismus Czech Legalismus German Κινεζικός νομικισμός Greek

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Legalism | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

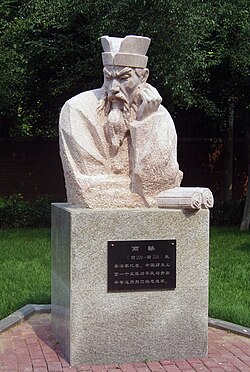

Statue of the legalist Shang Yang | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 法家 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | School of law | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Fajia (Chinese: 法家; pinyin: fǎjiā), or the School of fa (laws, methods), early translated as Legalism for Shang Yang,[1][2] is a school of thought representing a broader collection of mainly Warring States period classical Chinese philosophy, addressing practical governance challenges during a time when traditional feudal systems were collapsing. Incorporating more administrative works traditionally said to be rooted in Huang-Lao Daoism,[3] their ideas 'contributed greatly to the formation of the Chinese empire' and bureaucracy,[4] advocating concepts including rule by law, sophisticated administrative technique, and ideas of state power.[5] They are often interpreted in the West along realist lines.[6] The Qin to Tang were more characterized by their traditions.

The school incorporates the more Legalistic Li Kui and Shang Yang, and more administrative Shen Buhai and Shen Dao,[7] with Shen Buhai, Shen Dao, and Han Fei traditionally said to be rooted in Huang-Lao (Daoism), as attested by Sima Qian.[3] Shen Dao may have been a significant early influence for Daoism and administration.[8] These earlier currents were synthesized in the Han Feizi,[9][10] including some of the earliest commentaries on the Daoist text Daodejing. The later Han dynasty took Guan Zhong to be a forefather of the school, with the Guanzi added later. Later dynasties regarded Xun Kuang as a teacher of Han Fei and Qin Chancellor Li Si, as attested by Sima Qian.[11]

With a formative influence on Chinese law, Shang Yang's reforms transformed Qin from a peripheral power into a strongly centralized, militarily powerful kingdom, ultimately unifying China in 221 BCE. While Chinese administration cannot be traced to a single source, Shen Buhai's ideas significantly contributed to the meritocratic system later adopted by the Han dynasty. Sun Tzu's Art of War recommends Han Fei's concepts of power, technique, wu wei inaction, and impartiality, punishment and reward. With an impact beyond the Qin dynasty, despite a harsh reception in later times, succeeding emperors and reformers often recalled the templates set by Han Fei, Shen Buhai and Shang Yang, resurfacing as features of Chinese governance even as later dynasties officially embraced Confucianism.[12]

- ^ Creel 1982, p. 93,119–120; Needham 1978, p. 274; Goldin 2011; Jiang 2021, p. 234; Pines 2023; Hansen 1992, p. 13,345-347; Leung 2019, p. 103.

- ^ The origin of the term Legalism is unknown, but was reiterated by Needham with a focus on Shang Yang. Creel argued Shang Yang more Legalist, and Shen Buhai more administrative. With Shang Yang's reforms broader than law, as early argued by Schwartz, it has since been derogated in scholarship.

- ^ a b Peerenboom 1993, p. 1; Creel 1982, p. 49; Schwartz 1985, p. 237; Kejian 2016, p. 22,184.

- ^ Pines 2023.

- ^ Fraser 2011, p. 59,66; Goldin 2011, p. 91-92,96; Pines 2023; Jiang 2021, p. 237; Graham 1989, p. 268,282-283; Hansen 1992, pp. 364, 347, 350; Creel 1982, p. 81,93-95,103; Yu 2024, p. 58-59.

- ^ Pines 2023; Fraser 2011, p. 59; Harris 2022.

- ^ Fraser 2011, p. 63; Jiang 2021, p. 236; Goldin 2011, p. 91-92.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Fraser 2011, p. 64; Goldin 2011, p. 91-92,96.

- ^ Goldin 2011, p. 95-96.

- ^ Lundahl 1992 Although a given in the west, Chinese scholars did not regard the entire Han Feizi as written by Han Fei either. They regarded the pseudonymous Han Fei as one major author. It likely includes the sympathetic material of at least one other later emissary. The Daodejing commentaries are typically taken as addendums.

- ^ Goldin 2018; Goldin 2012, p. 164.

- ^ Shang Yang's mutual responsibility groups for instance were not a permanent feature of Chinese governance, but were implemented in times of disorder as late as Ding Richang, with "Baojia" or mutual responsibility a likely example. Mutual responsibility existed in Li Shanchang's time before a new dynastic legal code was drawn up.