Back Christenverfolgung ALS اضطهاد المسيحيين Arabic Persecució dels cristians Catalan چەوساندنەوەی مەسیحییەکان CKB Pronásledování křesťanů Czech Kristenforfølgelse Danish Christenverfolgung German Persekutado de kristanoj Esperanto Persecución a los cristianos Spanish آزار مسیحیان Persian

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

The persecution of Christians can be historically traced from the first century of the Christian era to the present day. Christian missionaries and converts to Christianity have both been targeted for persecution, sometimes to the point of being martyred for their faith, ever since the emergence of Christianity.

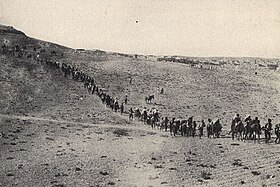

Early Christians were persecuted at the hands of both Jews, from whose religion Christianity arose, and the Romans who controlled many of the early centers of Christianity in the Roman Empire. Since the emergence of Christian states in Late Antiquity, Christians have also been persecuted by other Christians due to differences in doctrine which have been declared heretical. Early in the fourth century, the empire's official persecutions were ended by the Edict of Serdica in 311 and the practice of Christianity legalized by the Edict of Milan in 312. By the year 380, Christians had begun to persecute each other. The schisms of late antiquity and the Middle Ages – including the Rome–Constantinople schisms and the many Christological controversies – together with the later Protestant Reformation provoked severe conflicts between Christian denominations. During these conflicts, members of the various denominations frequently persecuted each other and engaged in sectarian violence. In the 20th century, Christian populations were persecuted, sometimes, they were persecuted to the point of genocide, by various states, including the Ottoman Empire and its successor state Turkey, which committed the Hamidian massacres, the Armenian genocide, the Assyrian genocide, the Greek genocide, and the Diyarbekir genocide, and atheist states such as those of the former Eastern Bloc.

The persecution of Christians has continued to occur during the 21st century. Christianity is the largest world religion and its adherents live across the globe. Approximately 10% of the world's Christians are members of minority groups which live in non-Christian-majority states.[10] The contemporary persecution of Christians includes the official state persecution mostly occurring in countries which are located in Africa and Asia because they have state religions or because their governments and societies practice religious favoritism. Such favoritism is frequently accompanied by religious discrimination and religious persecution.

According to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom's 2020 report, Christians in Burma, China, Eritrea, India, Iran, Nigeria, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Vietnam are persecuted; these countries are labelled "countries of particular concern" by the United States Department of State, because of their governments' engagement in, or toleration of, "severe violations of religious freedom".[11]: 2 The same report recommends that Afghanistan, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, the Central African Republic, Cuba, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Sudan, and Turkey constitute the US State Department's "special watchlist" of countries in which the government allows or engages in "severe violations of religious freedom".[11]: 2

Much of the persecution of Christians in recent times is perpetrated by non-state actors which are labelled "entities of particular concern" by the US State Department, including the Islamist groups Boko Haram in Nigeria, the Houthi movement in Yemen, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant – Khorasan Province in Pakistan, al-Shabaab in Somalia, the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Islamic State as well as the United Wa State Army and participants in the Kachin conflict in Myanmar.[11]: 2

- ^ Bulut, Uzay (30 August 2024). "Turkey: Ongoing Violations against Greek Christians". The European Conservative. Budapest, Brussels, Rome, Vienna: Center for European Renewal. ISSN 2590-2008. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Morris, Benny; Ze'evi, Dror (4 November 2021). "Then Came the Chance the Turks Have Been Waiting For: To Get Rid of Christians Once and for All". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Morris, Benny; Ze'evi, Dror (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-674-24008-7.

- ^ Gutman, David (2019). "The thirty year genocide: Turkey's destruction of its Christian minorities, 1894–1924". Turkish Studies. 21 (1). London and New York: Routledge on behalf of the Global Research in International Affairs Center: 1–3. doi:10.1080/14683849.2019.1644170. eISSN 1743-9663. ISSN 1468-3849. S2CID 201424062.

- ^ Smith, Roger W. (Spring 2015). "Introduction: The Ottoman Genocides of Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks". Genocide Studies International. 9 (1). Toronto: University of Toronto Press: 1–9. doi:10.3138/GSI.9.1.01. ISSN 2291-1855. JSTOR 26986011. S2CID 154145301.

- ^ Roshwald, Aviel (2013). "Part II. The Emergence of Nationalism: Politics and Power – Nationalism in the Middle East, 1876–1945". In Breuilly, John (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 220–241. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199209194.013.0011. ISBN 9780191750304.

- ^ Üngör, Uğur Ümit (June 2008). "Seeing like a nation-state: Young Turk social engineering in Eastern Turkey, 1913–50". Journal of Genocide Research. 10 (1). London and New York: Routledge: 15–39. doi:10.1080/14623520701850278. ISSN 1469-9494. OCLC 260038904. S2CID 71551858.

- ^ İçduygu, Ahmet; Toktaş, Şule; Ali Soner, B. (February 2008). "The politics of population in a nation-building process: Emigration of non-Muslims from Turkey". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 31 (2). London and New York: Routledge: 358–389. doi:10.1080/01419870701491937. ISSN 1466-4356. OCLC 40348219. S2CID 143541451. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

- ^ PEW (19 December 2011). "Living as Majorities and Minorities". Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population. Pew Research Center Religion and Public Life. p. 3. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

If all these Christians were in a single country, it would have the second-largest Christian population in the world, after the United States.

- ^ a b c "Annual Report 2020" (PDF). United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. pp. 1, 11.