Back يوم الحراك المباشر Arabic কলকাতা দাঙ্গা Bengali/Bangla Unruhen in Kalkutta 1946 German कलकत्ता दंगा Hindi Hari Aksi Langsung ID Great Calcutta Killing Italian പ്രത്യക്ഷ കർമ്മ ദിനം Malayalam Direct Action Day Dutch Dzień Akcji Bezpośredniej Polish День прямого действия Russian

| Direct Action Day 1946 Calcutta Killings | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Partition of India | |||

| |||

| Date | 16 August 1946 | ||

| Location | 22°35′N 88°22′E / 22.58°N 88.36°E | ||

| Caused by | Impending division of Bengal on religious grounds | ||

| Goals | Ethnic and religious persecution | ||

| Methods | Massacre, pogrom, forced conversion, arson, abduction and mass rape | ||

| Resulted in | Partition of Bengal | ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

No centralized leadership | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 4,000[3][4] | ||

| Part of a series on |

| Persecution of Hindus in pre-1947 India |

|---|

| Issues |

| Incidents |

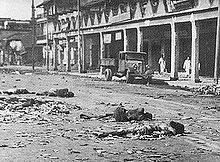

Direct Action Day (16 August 1946) was the day the All-India Muslim League decided to take "direct action" for a separate Muslim homeland after the British exit from India. Also known as the 1946 Calcutta Killings, it was a day of nationwide communal riots.[5] It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hindus in the city of Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) in the Bengal province of British India.[3] The day also marked the start of what is known as The Week of the Long Knives.[6][7] While there is a certain degree of consensus on the magnitude of the killings (although no precise casualty figures are available), including their short-term consequences, controversy remains regarding the exact sequence of events, the various actors' responsibility and the long-term political consequences.[8]

There is still extensive controversy regarding the respective responsibilities of the two main communities, the Hindus and the Muslims, in addition to individual leaders' roles in the carnage. The dominant British view tends to blame both communities equally and to single out the calculations of the leaders and the savagery of the followers, amongst whom there were criminal elements.[citation needed] In the Indian National Congress' version of the events, the blame tends to be laid squarely on the Muslim League and in particular on the Chief Minister of Bengal, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy.[9] The view from the Muslim League is that Congress and the Hindus in fact used the opportunity offered by Direct Action Day to teach the Muslims in Calcutta a lesson and to kill them in great numbers.[citation needed] Thus, the riots opened the way to a partition of Bengal between a Hindu-dominated Western Bengal including Calcutta and a Muslim-dominated Eastern Bengal (now Bangladesh).[8]

The All-India Muslim League and the Indian National Congress were the two largest political parties in the Constituent Assembly of India in the 1940s. The Muslim League had demanded since its 1940 Lahore Resolution for the Muslim-majority areas of India in the northwest and the east to be constituted as 'independent states'. The 1946 Cabinet Mission to India for planning of the transfer of power from the British Raj to the Indian leadership proposed a three-tier structure: a centre, groups of provinces and provinces. The "groups of provinces" were meant to accommodate the Muslim League's demand. Both the Muslim League and the Congress in principle accepted the Cabinet Mission's plan.[10] However, the Muslim League suspected the Congress's acceptance to be insincere.

Consequently, in July 1946, the Muslim League withdrew its agreement to the plan and announced a general strike (hartal) on 16 August, terming it Direct Action Day, to assert its demand for a separate homeland for Muslims in certain northwestern and eastern provinces in colonial India.[11][12] Calling for Direct Action Day, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the All India Muslim League, said that he wanted "either a divided India or a destroyed India".[13][14]

Against a backdrop of communal tension, the protest triggered massive riots in Calcutta.[15][16] More than 4,000 people died and 100,000 residents were left homeless in Calcutta within 72 hours.[3][4] The violence sparked off further religious riots in the surrounding regions of Noakhali, Bihar, United Provinces (modern day Uttar Pradesh), Punjab (including massacres in Rawalpindi) and the North Western Frontier Province.[17] The events sowed the seeds for the eventual Partition of India.

- ^ Sarkar, Tanika; Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2017). Calcutta: The Stormy Decades. Taylor & Francis. p. 441. ISBN 978-1-351-58172-1.

- ^ Wavell, Archibald P. (1946). Report to Lord Pethick-Lawrence. British Library Archives: IOR.

- ^ a b c Burrows, Frederick (1946). Report to Viceroy Lord Wavell. The British Library IOR: L/P&J/8/655 f.f. 95, 96–107.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Tanika; Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2017). Calcutta: The Stormy Decades. Taylor & Francis. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-351-58172-1.

- ^ Zehra, Rosheena (16 August 2016). "Direct Action Day: When Massive Communal Riots Made Kolkata Bleed". TheQuint. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ Sengupta, Debjani (2006). "A City Feeding on Itself: Testimonies and Histories of 'Direct Action' Day" (PDF). In Narula, Monica (ed.). Turbulence. Serai Reader. Vol. 6. The Sarai Programme, Center for the Study of Developing Societies. pp. 288–295. OCLC 607413832.

- ^ L/I/1/425. The British Library Archives, London.

- ^ a b "The Calcutta Riots of 1946 | Sciences Po Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network". www.sciencespo.fr. 4 April 2019.

- ^ Harun-or-Rashid (2003) [First published 1987]. The Foreshadowing of Bangladesh: Bengal Muslim League and Muslim Politics, 1906–1947 (Revised and enlarged ed.). The University Press Limited. pp. 242, 244–245. ISBN 984-05-1688-4.

- ^ Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Nariaki, Nakazato (2000). "The politics of a Partition Riot: Calcutta in August 1946". In Sato Tsugitaka (ed.). Muslim Societies: Historical and Comparative Aspects. Routledge. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-415-33254-5.

- ^ Bourke-White, Margaret (1949). Halfway to Freedom: A Report on the New India in the Words and Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White. Simon and Schuster. p. 15.

- ^ Guha, Ramachandra (23 August 2014). "Divided or Destroyed – Remembering Direct Action Day". The Telegraph (Opinion).

- ^ Tunzelmann, Alex von (2012). Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4711-1476-2.

- ^ Das, Suranjan (May 2000). "The 1992 Calcutta Riot in Historical Continuum: A Relapse into 'Communal Fury'?". Modern Asian Studies. 34 (2): 281–306. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0000336X. JSTOR 313064. S2CID 144646764.

- ^ Das, Suranjan (2012). "Calcutta Riot, 1946". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009), The Partition of India, Cambridge University Press, p. 67, ISBN 978-0-521-67256-6,

(Signs of 'ethnic cleansing') were also present in the wave of violence that rippled out from Calcutta to Bihar, where there were high Muslim casualty figures, and to Noakhali deep in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta of Bengal. Concerning the Noakhali riots, one British officer spoke of a 'determined and organized' Muslim effort to drive out all the Hindus, who accounted for around a fifth of the total population. Similarly, the Punjab counterparts to this transition of violence were the Rawalpindi massacres of March 1947. The level of death and destruction in such West Punjab villages as Thoa Khalsa was such that communities couldn't live together in its wake.