Back Cròniques de Froissart Catalan Froissarts Krøniker Danish Crónicas de Froissart Spanish Chroniques (Froissart) French Kronik Froissart ID Cronache di Froissart Italian Historiarum opus (Frossardus) Latin Kroniek van Froissart Dutch Croniques (Froissart) PCD Crônicas de Froissart Portuguese

Froissart's Chronicles (or Chroniques) are a prose history of the Hundred Years' War written in the 14th century by Jean Froissart. The Chronicles open with the events leading up to the deposition of Edward II in 1327, and cover the period up to 1400, recounting events in western Europe, mainly in England, France, Scotland, the Low Countries and the Iberian Peninsula, although at times also mentioning other countries and regions such as Italy, Germany, Ireland, the Balkans, Cyprus, Turkey and North Africa.

For centuries the Chronicles have been recognized as the chief expression of the chivalric culture of 14th-century England and France. Froissart's work is perceived as being of vital importance to informed understandings of the European 14th century, particularly of the Hundred Years' War. But modern historians also recognize that the Chronicles have many shortcomings as a historical source: they contain erroneous dates, have misplaced geography, give inaccurate estimations of sizes of armies and casualties of war, and may be biased in favour of the author's patrons.

Although Froissart is sometimes repetitive or covers seemingly insignificant subjects, his battle descriptions are lively and engaging. For the earlier periods Froissart based his work on other existing chronicles, but his own experiences, combined with those of interviewed witnesses, supply much of the detail of the later books. Although Froissart may never have been in a battle, he visited Sluys in 1386 to see the preparations for an invasion of England. He was present at other significant events such as the baptism of Richard II in Bordeaux in 1367, the coronation of King Charles VI of France in Rheims in 1380, the marriage of Duke John of Berry and Jeanne of Boulogne in Riom and the joyous entry of the French queen Isabeau of Bavaria in Paris, both in 1389.

Sir Walter Scott once remarked that Froissart had "marvellous little sympathy" for the "villain churls".[1] It is true that Froissart often omits to talk about the common people, but that is largely the consequence of his stated aim to write not a general chronicle but a history of the chivalric exploits that took place during the wars between France and England. Nevertheless, Froissart was not indifferent to the wars' effects on the rest of society. His Book II focuses extensively on popular revolts in different parts of western Europe (France, England and Flanders) and in this part of the Chronicles the author often demonstrates good understanding of the factors that influenced local economies and their effect on society at large; he also seems to have a lot of sympathy in particular for the plight of the poorer strata of the urban populations of Flanders.[2]

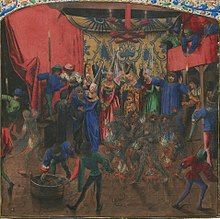

The Chronicles are a very extensive work: with their almost 1.5 million words, they are amongst the longest works written in French prose in the late Middle Ages.[3] Few modern complete editions have been published, but the text was printed from the late 15th century onwards. Enguerrand de Monstrelet continued the Chronicles to 1440, while Jean de Wavrin incorporated large parts of it in his own work. Robert Gaguin's Compendium super origine et gestis Francorum made ample use of Froissart.[4] In the 15th and 16th centuries the Chronicles were translated into Dutch, English, Latin, Spanish, Italian and Danish. The English translation, dated 1523–1525 and carried out by the then-Lord Berners, is one of the oldest historical prose works in English.[5] The text of Froissart's Chronicles is preserved in more than 150 manuscripts, many of which are illustrated, some extensively.[6]

- ^ Sir Walter Scott: Tales of my landlord. As used here, "villain" means "villein".

- ^ Peter Ainsworth, 'Froissardian perspectives on late-fourteenth-century society', in Jeffrey Denton and Brian Pullan (eds.), Orders and Hierarchies in Late Medieval and Renaissance Europe (Basingstoke / London: Macmillan Press, 1999), pp. 56-73.

- ^ Croenen, Godfried. "Online Froissart". HRIOnline. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ Franck Collart, Un historien au travail à la fin du XVe siècle: Robert Gaguin (Geneva: Droz, 1996), 121-122, 341-344.

- ^ Kane, George (1986). "An Accident of History: Lord Berners's Translation of Froissart's "Chronicles"". The Chaucer Review. 21 (2): 217–225. JSTOR 25093996. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Godfried Croenen, 'Froissart illustration cycles', in Graeme Dunphy (ed.), The Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle (Leiden: Brill, 2010), I, 645-650.