Back الصفقة الجديدة Arabic New Deal AST Ruzveltin yeni kursu Azerbaijani Новы курс Рузвельта Byelorussian Нов курс на Рузвелт Bulgarian New Deal BS New Deal Catalan New Deal Czech Y Fargen Newydd Welsh New Deal Danish

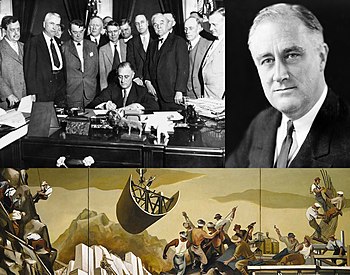

Top left: The TVA Act signed into law in 1933 Top right: President Franklin D. Roosevelt led the New Dealers; Bottom: A public mural from the arts program | |

| Location | United States |

|---|---|

| Type | Economic program |

| Cause | Great Depression |

| Organized by | President Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Outcome | Reform of Wall Street; relief for farmers and unemployed; social security; political power shifts to Democratic New Deal Coalition |

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938. Major federal programs and agencies, including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) and the Social Security Administration (SSA), provided support for farmers, the unemployed, youth, and the elderly. The New Deal included new constraints and safeguards on the banking industry and efforts to re-inflate the economy after prices had fallen sharply. New Deal programs included both laws passed by Congress as well as presidential executive orders during the first term of the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The programs focused on what historians refer to as the "3 R's": relief for the unemployed and for the poor, recovery of the economy back to normal levels, and reform of the financial system to prevent a repeat depression.[1] The New Deal produced a political realignment, making the Democratic Party the majority (as well as the party that held the White House for seven out of the nine presidential terms from 1933 to 1969) with its base in progressive ideas, the South, big city machines and the newly empowered labor unions, and various ethnic groups. The Republicans were split, with progressive Republicans in support but conservatives opposing the entire New Deal as hostile to business and economic growth. The realignment crystallized into the New Deal coalition that dominated presidential elections into the 1960s and the opposing conservative coalition largely controlled Congress in domestic affairs from 1937 to 1964.

Roosevelt was supportive of the idea of creating a progressive Democratic Party that could lure away progressives from the Republican Party. Indeed, Roosevelt had appealed to progressive Republicans for support for New Deal programs. As noted by one historian, however, there were limits "as to how far Roosevelt would go to establish a unified progressive party. He would not actively support progressive candidates in Senate and House electoral contests if the progressive was a Republican. The most notable example of this was his hands-off policy in a Pennsylvania Senate election despite an appeal by Gifford Pinchot, a prominent progressive and friend of Roosevelt, for help. Reluctant to alienate the conservative wing of the Democratic Party, Roosevelt at least made this minimal concession to party loyalty. He was willing to manage the tensions between ideology and party as long as progressives predominated in Congress and some Southern conservative Democrats were willing to trade their support for New Deal economic programs for federal tolerance of racial discrimination in the South. A prudent balancing of the conflicting demands of party and ideology at this time served the end of furthering his own reform agenda."[2]

- ^ Carol Berkin; et al. (2011). Making America, Volume 2: A History of the United States: Since 1865. Cengage Learning. pp. 629–632. ISBN 978-0-495-91524-9.

- ^ Corporatism and the Rule of Law A Study of the National Recovery Administration By Donald R. Brand, 2019, P.62-63