Back توماس هارت بنتون (سياسي) Arabic توماس هارت بنتون ARZ توماس هارت بنتون AZB Thomas Hart Benton (polític) Catalan Thomas Hart Benton (Politiker) German Thomas Hart Benton (político) Spanish توماس هارت بنتون Persian Thomas Hart Benton (homme politique) French Thomas Hart Benton (politikus) ID Thomas Hart Benton (politico) Italian

Thomas Hart Benton | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Missouri | |

| In office August 10, 1821 – March 3, 1851 | |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Henry S. Geyer |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1853 – March 3, 1855 | |

| Preceded by | John F. Darby |

| Succeeded by | Luther M. Kennett |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 14, 1782 Orange County, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | April 10, 1858 (aged 76) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (Before 1825) Jacksonian (1825–1837) Democratic (1837–1858) |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Preston McDowell |

| Relatives | John C. Frémont (son-in-law) |

| Education | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1812–1815 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

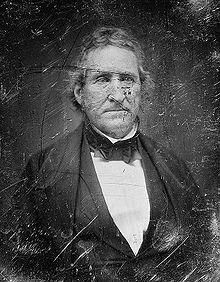

Thomas Hart Benton (March 14, 1782 – April 10, 1858), nicknamed "Old Bullion", was an American politician, attorney, soldier, and longtime United States Senator from Missouri. A member of the Democratic Party, he was an architect and champion of westward expansion by the United States, a cause that became known as manifest destiny. Benton served in the Senate from 1821 to 1851, becoming the first member of that body to serve five terms. He was born in North Carolina.

After being expelled from the University of North Carolina in 1799 for theft,[1] he established a law practice and plantation near Nashville, Tennessee. He served as an aide to General Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812 and settled in St. Louis, Missouri, after the war. Missouri became a state in 1821, and Benton won election as one of its inaugural pair of United States Senators. The Democratic-Republican Party fractured after 1824, and Benton became a Democratic leader in the Senate, serving as an important ally of President Jackson and President Martin Van Buren. He supported Jackson during the Bank War and proposed a land payment law that inspired Jackson's Specie Circular executive order.

Benton's prime concern was the westward expansion of the United States. He called for the annexation of the Republic of Texas, which was accomplished in 1845. He pushed for compromise in the partition of Oregon Country with the British and supported the 1846 Oregon Treaty, which divided the territory along the 49th parallel. He also authored the first Homestead Act, which granted land to settlers willing to farm it.

Though he owned slaves,[2] Benton came to oppose the institution of slavery after the Mexican–American War, and he opposed the Compromise of 1850 as too favorable to pro-slavery interests. This stance damaged Benton's popularity in Missouri, and the state legislature denied him re-election in 1851. Benton won election to the United States House of Representatives in 1852 but was defeated for re-election in 1854 after he opposed the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Benton's son-in-law, John C. Frémont, won the 1856 Republican Party nomination for president, but Benton voted for James Buchanan and remained a loyal Democrat until his death in 1858.

- ^ Documenting the American South: Benton, Thomas Hart, 2005, retrieved December 2, 2023

- ^ "Congress slaveowners", The Washington Post, January 27, 2022, retrieved January 31, 2022