Back Curgyld þāra Geāndena Rīca American ANG المجمع الانتخابي (الولايات المتحدة) Arabic Botong elektoral BCL Калегія выбаршчыкаў (ЗША) Byelorussian Избирателна колегия (САЩ) Bulgarian ইলেকটোরাল কলেজ (মার্কিন যুক্তরাষ্ট্র) Bengali/Bangla Col·legi Electoral dels Estats Units Catalan Тӳре-суйлавçăсен коллегийĕ CV Coleg Etholiadol UDA Welsh Valgmandskollegiet (USA) Danish

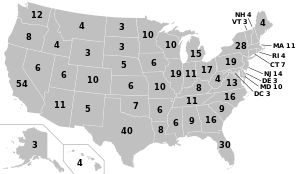

In Maine (upper-right) and Nebraska (center), the small circled numbers indicate congressional districts. These are the only 2 states to use a district method for some of their allocated electors, instead of a complete winner-takes-all party block voting.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States |

|---|

|

In the United States, the Electoral College is the group of presidential electors that is formed every four years for the sole purpose of voting for the president and vice president. The process is described in Article II of the U.S. Constitution.[1] Each state appoints electors using legal procedures determined by its legislature, equal in number to its congressional delegation (representatives and senators) totaling 535 electors. A 1961 amendment granted the federal District of Columbia three electors. Of the current 538 electors, a simple majority of 270 or more electoral votes is required to elect the president and vice president. If no candidate achieves a majority there, a contingent election is held by the House of Representatives to elect the president and by the Senate to elect the vice president. Federal office holders, including senators and representatives, cannot be electors.

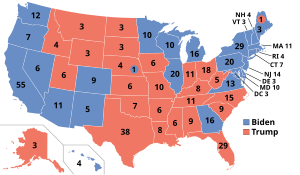

The states and the District of Columbia hold a statewide or district-wide popular vote on Election Day in November to choose electors based upon how they have pledged to vote for president and vice president, with some state laws prohibiting faithless electors. All states except Maine and Nebraska use a party block voting, or general ticket method, to choose their electors, meaning all their electors go to one winning ticket. Maine and Nebraska choose one elector per congressional district and 2 electors for the ticket with the highest statewide vote. The electors meet and vote in December, and the inauguration of the president and vice president take place in January.

The merits of the electoral college system is a matter of ongoing debate in the United States since its inception at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, becoming more controversial by the latter years of the 19th century, up through to the present day.[2][3] More resolutions have been submitted to amend the Electoral College mechanism than any other part of the constitution,[4] with 1969–70 as the closest attempt to reform the Electoral College.[5]

Supporters argue that it requires presidential candidates to have broad appeal across the country to win, while critics argue that it is not representative of the popular will of the nation.[a] Winner-take-all systems, especially with representation not proportional to population, do not align with the principle of "one person, one vote".[b][9] Critics object to the inequity that, due to the distribution of electors, individual citizens in states with smaller populations have more voting power than those in larger states.[10] This is because the number of electors each state appoints is equal to the size of its congressional delegation, each state is entitled to at least 3 regardless of its population, and the apportionment of the statutorily fixed number of the rest is only roughly proportional. This allocation has contributed to runners-up of the nationwide popular vote being elected president in 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016.[11][12] In addition, faithless electors may not vote in accord with their pledge.[13][c] Further objection is that swing states receive the most attention from candidates.[15] By the end of the 20th century, Electoral colleges had been abandoned by all other democracies around the world in favor of direct elections for an executive president.[16][17]:215

- ^ "Article II". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Karimi, Faith (October 10, 2020). "Why the Electoral College has long been controversial". www.cnn.com/. CNN. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ Keim, Andy. "Mitch McConnell Defends the Electoral College". www.myheritage.org/. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ Bolotnikova, Marina N. (July 6, 2020). "Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?". Harvard Magazine.

- ^ Ziblatt, Daniel; Levitsky, Steven (September 5, 2023). "How American Democracy Fell So Far Behind". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Beeman 2010, pp. 129–130

- ^ Beeman 2010, p. 135

- ^ Guelzo, Allen (April 2, 2018). "In Defense of the Electoral College". National Affairs. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ Lounsbury, Jud (November 17, 2016). "One Person One Vote? Depends on Where You Live". The Progressive. Madison, Wisconsin: Progressive, Inc. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Speel, Robert (November 15, 2016). "These 3 Common Arguments For Preserving the Electoral College Are All Wrong". Time. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

"Rural states get a slight boost from the 2 electoral votes awarded to states due to their 2 Senate seats

- ^ Neale, Thomas H. (October 6, 2017). "Electoral College Reform: Contemporary Issues for Congress" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Mahler, Jonathan; Eder, Steve (November 10, 2016). "The Electoral College Is Hated by Many. So Why Does It Endure?". The New York Times. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ West, Darrell M. (2020). "It's Time to Abolish the Electoral College" (PDF).

- ^ "Should We Abolish the Electoral College?". Stanford Magazine. September 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Tropp, Rachel (February 21, 2017). "The Case Against the Electoral College". Harvard Political Review. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Collin, Richard Oliver; Martin, Pamela L. (January 1, 2012). An Introduction to World Politics: Conflict and Consensus on a Small Planet. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442218031.

- ^ Levitsky, Steven; Ziblatt, Daniel (2023). Tyranny of the Minority: why American democracy reached the breaking point (First ed.). New York: Crown. ISBN 978-0-593-44307-1.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).